Opened in Detroit. Mich., through efforts of the Detroit League on Urban Conditions Among Negroes.

The Survey, vol 40, no. 5, May 1918, pp. 115–122.

115 The present migration of Negroes from the South is another chapter in the story of the masses struggling to secure better conditions of living and larger life.

This movement northward is vitally changing the South, the North, and the Negroes themselves, North and South. The facts should be studied therefore sympathetically and frankly to arrive at “a complete understanding and cooperation of all forces. North and South, white and black, that are Ln the last analysis necessary to the right solution of a nation-wide problem with its nation-wide responsibility.”

The geographical and numerical extent of this migration has been large. The movement is due to fundamental economic and social forces. It has already produced such far-reaching effects in the South that remedies are now being sought and applied. The part of this question which pertains more nearly to the South will be discussed here, and the part which relates to the North in a later article.

This migration during the past two years is the second large exodus since Lincoln’s memorable Emancipation Proclamation. A constant, fluctuating stream, a part of the drift of the general population from the rural districts to the cities, was moving northward from 1875 until 1915. This followed an exodus between 1865 and 1875 similar to the present one.

The breaking up of the plantation system based upon slavery and racial friction of Ku KIux and Reconstruction days were the moving causes of the striking increase of that period. Between 1890 and 1900 there was also a considerable increase in the movement, probably due to the economic and social disturbances of the decade.

The fact that there has been a constant movement northward is shown by the percentage of increase, based upon the United States census figures, of Negro population during each decade since 1860 for nine of the northern and border cities, as follows: Boston, Greater New York, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Chicago, Cincinnati, Indianapolis, Evansville and St. Louis. Between 1860 and 1870 the Negro population increased about 51 per cent (for eight cities); from 1870 to 1880 about 36.4 per cent (for eight cities); from 1880 to 1890 about 36.2 per cent; from 1890 to 1900 about 74.4 per cent and from 1900 to 1910 about 37.4 per cent.

During this time the rate of increase for the total Negro population was as follows: 1860 to 1870, 9.9 per cent; 1870 to 1880, 34.9 par cent; 1880 to 1890, 13.5 per cent; 1890 to 1900, 18.0 per cent; 1900 to 1910, 11.2 per cent. A comparison of the increase of the Negro population in these northern cities with the increase of the total Negro population shows that the increase in the northern cities in four decades has been from nearly three times as large to about five times as large as the increase over the whole country.

The increase of the Negro population in southern cities which may be compared with the increase in northern cities for the same decades is as follows: From 1860 to 1870 about 90.7 per cent (for 14 cities); from 1870 to 1880 about 25.5 per cent (for 15 cities); from 1880 to 1890 about 38.9 per cent (for 15 cities); from 1890 to 1900 about 20.6 per cent (for 16 cities); and from 1900 to 1910 about 20.6 per cent (for 16 cities). The southern cities included are Wilmington, Baltimore, Washington, Norfolk, Richmond, Charleston, Augusta, Savannah, Louisville, Chattanooga, Nashville, Memphis, Birmingham (1900-1910), Mobile, New Orleans.

A comparison of the figures for northern and southern cities shows clearly that the movement northward has been and is a part of a general movement to cities. The migrants from rural districts, however, prefer northern cities. This is evident from the fact that in three of the five decades since 1860 the increase for northern cities exceeded that for southern cities, being 24.6 per cent greater between 1870 and 1880,53.8 per cent greater between 1890 and 1900 and 16.8 per cent greater between 1900 and 1910.

The Negroes’ preference for northern residence is even more clearly shown in the percentage increase of the Negro population by geographic divisions for ten-year periods from 1880 to 1910. The following table shows this fact:

| GEOGRAPHIC DIVISIONS | 1880-1890 | 1890-1900 | 1900-1910 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | New England | 11.7 | 32.6 | 12.2 |

| 2. | Middle Atlantic | 18.9 | 44.6 | 28.2 |

| 3. | East North Central | 12.9 | 24.S | 16.7 |

| 4. | West North Central | 10.8 | 6.2 | 2.0 |

| 5. | South Atlantic | 10.9 | 14.3 | 10.3 |

| 6. | East South Central | 10.1 | 17.9 | 6.1 |

| 7. | West South Central | 25.0 | 22.9 | 17.1 |

The New England, Middle Atlantic and East North Central divisions have had the largest increases in Negro population with two exceptions, and these two exceptions may be partly due to the large increase of Negroes in the Rocky Mountain and Pacific Coast geographical divisions. It is also significant that the increase during the last two decades has been greater in the New England, Middle Atlantic and East Central divisions than the increase of the total Negro population.

The extent of southern territory affected by the migration now in progress lies mainly east of the Mississippi river. Missouri, Arkansas, Oklahoma and Texas seem not to have suffered as yet. In fact, some of the migrants from Mississippi have gone to the rich “cotton-bottoms” counties of Arkansas along the Mississippi river, and to Oklahoma. Alabama and Georgia probably have been the biggest losers. Mississippi probably comes third; Florida probably fourth. The order of other southern states cannot now be approximately ascertained. However, North and South Carolina, Tennessee, Kentucky and Virginia have all furnished a considerable quota of the Negro migrants. During the past two years the writer has made extended visits to cities, towns and rural districts of all these states and has seen the character and effects of the movement of Negroes from these sections.

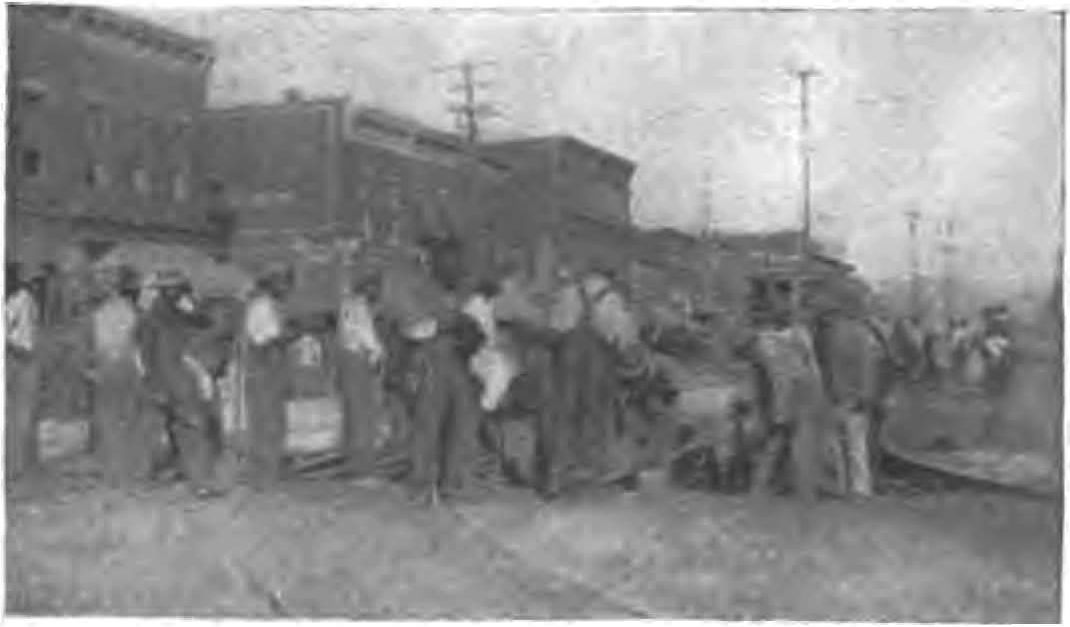

Perhaps there is no means of telling accurately how many have left the South. Numerical estimates have been made by some persons, based upon the statements of observers who have watched the trainloads leave, and upon the growth of numbers in different northern cities. Estimates based upon the records of insurance companies, railway ticket offices and of other sources have been made by others. These estimates have ranged from 250,000 to more than 750,000. The Negro population of some of the northern centers has increased from about one- to four-fold during the past eighteen months. For instance, careful estimates show that the Negro population of Detroit, Mich., has increased from about 6,000 to about 25,000. A conservative estimate at Cincinnati places the number of those arriving at about 25,000 during twelve months ending September, 1917. Cincinnati has been a distributing point for other centers, so that probably less than a fifth stayed in that city. A study of the Negro Migrant in Pittsburgh by Epstein estimates a “total probable new Negro population of 18,550 in 1917.” This is an increase of nearly 50 per cent. Estimates for Philadelphia range from 12,000 to 40,000: “Some weeks they have come almost by the trainload.” Weighing all the estimates and information from the various sources, it is probably safe to say that between 400,000 and 500,000 Negroes have migrated North during the past two years.

These migrants are composed apparently of three types of people. First, there are the less responsible characters, younger men for the most part, who readily respond to the promises of high wages and free transportation made by labor agents. A representative of one large railroad company reported that in 1916 they chose anyone willing to come and thus brought up about 13,000 Negro men. They reported they still had in their employ in January, 1917, less than 2,500 of them. From this type of migrant develops the “floater” or “bird of passage.”

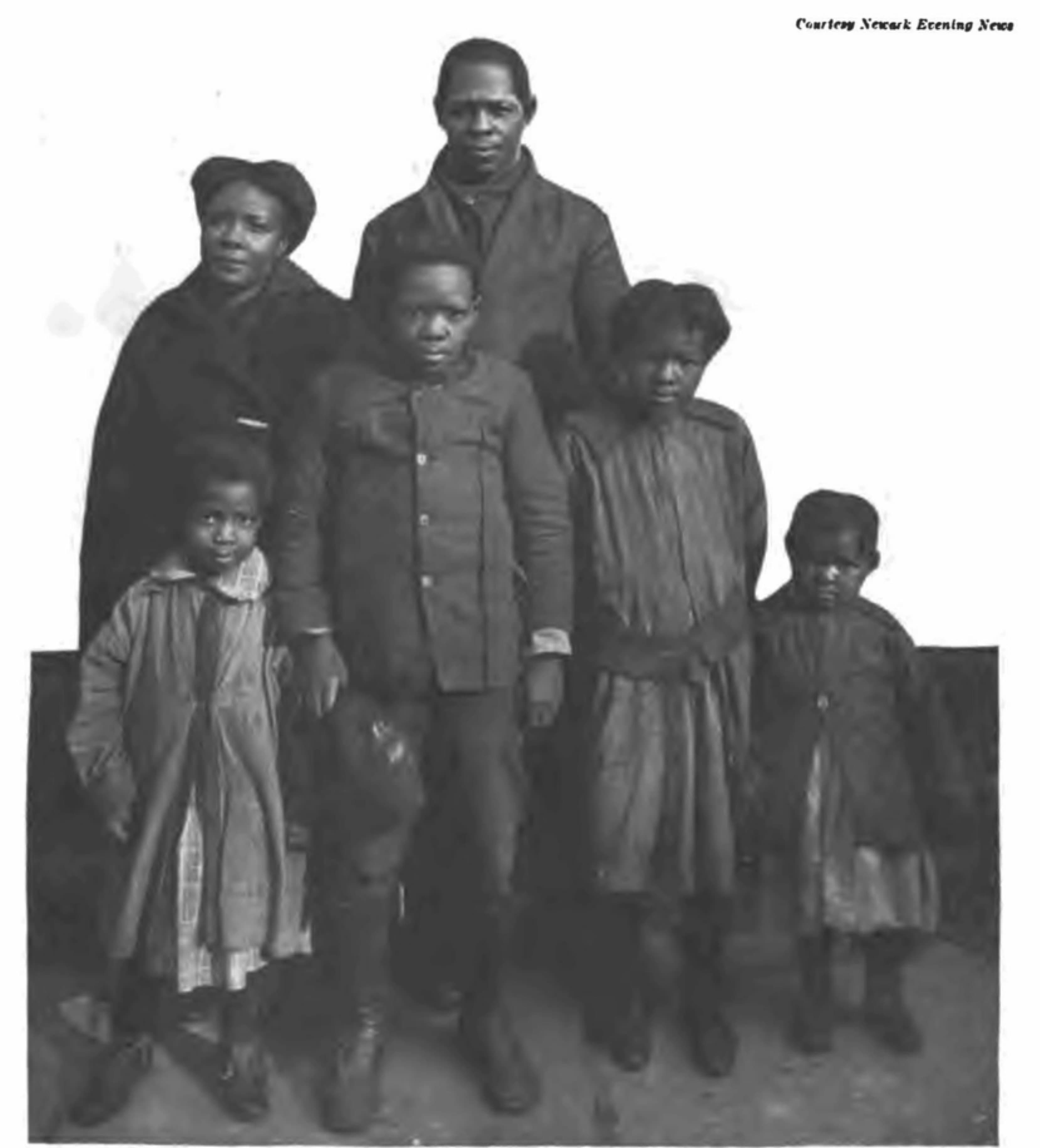

The second type of migrants consists of the industrious, thrifty, unskilled workers. Many of them are men with families or other dependents. They are looking for new homes. The men usually go first to earn money and look over the ground. Their families soon follow. Dissatisfied with the low wages, treatment and other conditions of their southern communities, many of these people accepted offers of work and free transportation. Considerable numbers had small savings, which were used to pay their traveling expenses. The writer visited several small towns in South Carolina and in Alabama, and saw companies of Negroes of this type leaving. Some parties included wives and children; in some groups only wives were accompanying their husbands and leaving their children with relatives. Neighbors were helping them pack their belongings and were sending them away with farewell greetings.

The third type of Negro migrant consists of skilled artisans business and professional men who share the dissatisfaction and restlessness of the southern Negro group. They feel also the necessity of going with the rank and file on whom they largely depend for patronage. Many of these people had considerable property. Highly skilled workmen and other new arrivals are known to have come to Michigan, Ohio and Massachusetts with fairly large sums of money from the sale of their possessions in the South. One professional man who had left Georgia summed up the feeling of this type by saying, “They are thrifty, have accumulated something out of their meager earnings. … They have gladly sacrificed their holdings to make this great step in the process of their emancipation.”

The fact that these three types of migrants have been going North and that the present migration is only an increase of a movement that has slowly been in progress for more than a generation leads naturally to a full discussion of the causes for this mass movement. The forces producing such an effect must be deep-seated and fundamental.

A study of the problem of migration to both northern and southern centers as it stood in 1912 and 1913 developed the thesis that the Negro is in the general population stream, and that, wherever similar causes operate under conditions similar to those moving the white population, the Negro, like the Caucasian, is coming to the city to stay. The divorce of the Negro from the soil and the call of commercial and industrial centers were the economic influences moving him, then, as they were moving his white fellow citizens. To these economic forces were added social and individual causes, such as the strained relations of landlords and tenants on southern plantations; “Jim Crow” legislation and other restrictions of 117the rights and privileges of persons of color. Influences such as the coming of labor agents, going North to join relatives, receipt of letters from those who had gone, visits from friends and relatives who had previously migrated North were noted as moving causes.1 The dramatic movement to northern industrial and commercial centers during the past two years has shown the effects of such forces and restrictions as those mentioned.

The whites have moved North in large numbers during the same time. Some of the causes moving the Negroes they have not felt; others they have. Their movement cannot now be easily traced, but the nativity figures of the next census may bring some interesting facts to light.

Observation and information gotten from various sources and during visits to seven of the southern states in 1916 and 1917 make the motives of the present migration clear. Those parts of Alabama which suffered from the effect of the boll-weevil were among those that felt the Negro migration most. When a month’s rain during the summer of 1916 gave the knockout stroke to the cotton crops that year, many planters are known to have advised their tenants to go somewhere to find work because the landlords could not “furnish them’’ until the next cropping season. The boll-weevil helped likewise to release the Negroes from the soil of Mississippi and Georgia. It is a sound inference then that those districts hard hit by boll-weevil, floods and other economic hardships for the past two years were among the districts that lost large numbers of their Negro population.

Simultaneous with these unfavorable economic conditions in southern districts there came an Unusual demand for labor in northern industrial centers. As is well known, these industrial centers were formerly supplied thousands of semi-skilled and unskilled European immigrants. The great war not only shut off an increase of this supply of laborers but also called some of those already here to the armies of their respective nations. At the time that foreigners went to join their colors, northern manufacturers received an unprecedented demand for war supplies. Northern railroad authorities, manufacturers and mine operators went in search of laborers. Imported Mexicans for railroad work were not successful. By careful selection and direction, one large railroad company found that 118 Negroes were satisfactory. Of about 3,000 brought North in 1916, about three-fourths were in their employ in 1917.

Soon labor agents were threading the South. They became the means of spreading information about the northern industrial opportunities, offering two dollars, three dollars, four dollars and five dollars a day. To southern Negro workmen who were averaging only one dollar to two dollars a day, and many of them less, the offers seemed magnificent, and few questions were asked about the cost of living, housing or other conditions.

These new economic influences have been important and powerful; they have not, however, been the only fundamental causes of the exodus. The Negro has sought larger protection to life and property and larger liberty. As the University Commission on Southern Race Questions said in 1917 in its Open Letter to the College Men of the South: “The dollar has lured the Negro to the East and North, as it has lured the white man even to the most inaccessible and forbidden regions of the earth. But the human being is moved and held not by money alone. Birthplace, home-ties, family, friends, associations and attachments of numerous kinds, fair treatment, opportunity to labor and enjoyment of the legitimate fruits of labor, assurance of even-handed justice in the courts, good educational facilities, sanitary living conditions, tolerance and sympathy—these things and, others like them make an even stronger appeal to the human mind and heart than does money.”

These words suggest to us another set of fundamental causes which have moved the Negroes to the North. The Negroes look to “the North” as to a “promised land” where these benefits may be obtained. This state of mind is clearly shown in reviewing a large number of letters they have written to persons in the North asking and urging to be given a chance to “better their conditions.” These letters express the desire to get a better job, to have a better home and to live a larger life. From Majette, Fla., a correspondent writes, “I no it is a good place in the North”; another from Atlanta, Ga., said, “My ambitions are such that (I) should be willing to do any kind of decent work in order to realize them”; another from Appalachia, Va., wrote, “It is a wearisome thing to work all the time and kan’t see or enjoy the fruits. …I wants to be some wheres I kin go to night school or day school either one.” Here is one from Raleigh, N. C.: “Willing to work at anything or place if there is a chance for advancement.” One from Macon, Ga., said, “I desire to go North to better my present condition.” Scores of others from various parts of the South wrote in the same strain.

A survey of the seven states mentioned in a preceding paragraph shows, furthermore, that those sections which have had lynchings, mobs and other race disturbances in recent years have lost large numbers of Negroes. Of course, the revolting cases of injustice at the hands of mobs occur in different localities at different times and therefore come directly under the attention of a limited number of Negroes. But two facts should be clearly understood.

We may look at these two facts in detail. First, the racial friction and lack of cooperation between many individuals in matters of everyday concern breed general discontent. The expression of good-will from the higher impulses of the two races is largely blocked by a multitude of petty restrictions and injustices that affect hundreds of Negroes in many localities. The inability to protect themselves against these many little injustices and indignities of everyday dealing in business and dvic life is the cause of much unrest and bitter feeling. A typical condition is shown in a Negro tenant’s reply to an inquiry about his affairs: “Boss I jes kan’t make enuff to feed my fam’ly.” “You seem to be pretty much alive,” answered his questioner, “how are you getting by?” “Why, my landlawd is a’vancin’ [furnishing rations] me. He’s done got me bought already fur nex’ yeah.” A bit of doggerel from the cotton fields shows the state of mind produced in the Negro:

And at the first suggestion he is ready to go North to try to find a home.

The fee system and lack of defense for the Negro in the inferior courts is also a great source of dissatisfaction and a great barrier to good-will. So generally is the court situation understood that some white men in one southern city have proposed starting a legal defense league with payments like industrial insurance to employ able lawyers to represent defenseless Negroes in the courts. Negroes also regard the denial of a voice in the government to which they pay taxes and to 119 which they loyally give themselves and their treasures in every emergency as another very serious matter.

The Negro has shown himself worthy of the measures of justice and expressions of good-will from his white fellow citizens. He has never attempted to assassinate an official of the government. He has never organized a strike when his country was at war. He has never been guilty of burning homes, arsenals, grain elevators and munition plants, even when war was being waged about his own enslavement. He would not poison or put glass into foodstuffs, or blow up hospital ships. He has given his blood and treasure in every war. Yet Negroes are lynched, burned at the stake and mobbed with impunity North and South, besides suffering the general exploitation of the weak the world over. Of course, conditions in different localities vary. In some sections relations of the races are amicable, and daily affairs move along in a more contented stream. The border states and the tide-water have many such communities.

In some sections of the South the best white citizens are voicing their belief in the Negro’s worth and their conviction against mob violence. For example, a statement was published recently in Memphis and Nashville signed by Bishop Gailor, Episcopal Bishop of Tennessee; by W. H. Litty, the mayor of Memphis; by Bolton Smith and Charles Haase, two prominent business men of Memphis. They said:

We are enlisting Negroes in our armies by the hundred thousand and sending them to France to fight for us. The Negroes furnish most of the labor for our farms and in our homes. We want them to stay in the South. Thoughtful southern men, who know conditions, want to give the good and respectable Negro a fair deal, and protect him in his life, liberty and property, and so encourage him to live and work among us. We believe that the mobs, who are yielding to their mad passions are working a terrible injury to the peace and prosperity of our country, and especially to this section of it.

Some of us are determined, therefore, to create if possible, a public opinion, that is just and enlightened, and that will frown down this evil; and with this in view, we ask you to meet with some of your fellow citizens on Friday, March 8, at 5 p. m., in Committee Room A, second floor, Chamber of Commerce, and discuss ways and means.

We may now consider the second fact in these reactions and opinions of Negroes about southern conditions. Negroes are more and more reading the white and Negro newspapers. The vivid descriptions of lynchings, mobs and other race disturbances are glaringly set forth in these newspapers. Little is said in the white press of the cooperation and good will between the races and the many excellent achievements of the Negroes. In homes, in barber-shops, pool-rooms and other places these accounts are read and discussed by Negroes. They make and leave the impression of insecurity to liberty, life and property. Certain lynchings in South Carolina, Georgia and Tennessee, in 1916, 1917 and 1918 were widely reported and discussed in Negro newspapers and periodicals. Not only vivid descriptions of the facts but also vigorous editorials against such outrages were widely circulated. Thousands of Negroes directly or indirectly all over the South felt the disturbance of mind produced by such occurrences. In the mind of the average Negro it is not the probability of being assaulted on slight provocation with little chance for defense or of being mobbed whether guilty or not, with no opportunity to prove an alibi, but it is the possibility of either occurrence that makes life and liberty uncertain and happiness impossible.

That the average southern Negro says little or nothing in protest against these injustices is no evidence that he does not feel them and remember them. His protest is not of the militant, Anglo-Saxon type. At his first opportunity he “folds his tent like the Arab and as silently steals away.” Scores of illustrations are available to show that the Negro has reacted to the situation and is in a dissatisfied state of mind. The interpretation of a Negro in Mississippi is that the Negro has two privileges—“ter pay his taxes and ter git out o’ de road.”

It is no exaggeration to say that the feeling of dissatisfaction with such conditions is widespread. Conversations with Negro leaders, artisans, laborers, railroad porters, farmers, tenants and field-hands have left this strong inference. Other persons besides the writer furnished some of the reports of these conversations. One of the foremost Negro leaders said: “The present administration of law in the South removes from the colored man the hope of protection in the right and from the white man the fear of punishment in wrong. This is a fact of mal-adjustment that double crosses both races.” One southern white man says, “The striking fact was the uniformity of the answers given by country Negroes and by Negro leaders alike. And fully half of the representative white men with whom I talked agreed with the Negroes.” This does not mean that the masses of Negroes have done any great reflection and philosophizing about the race problem. They have not. They have merely felt pain and the 120 pleasure of everyday life in their own localities. They have made immediate reactions to these concrete conditions. And many of them, when the chance came, silently moved away. A southern field-hand showed his idea of the cause of these reactions by singing as he followed the plow:

The education of their children is another matter which is disturbing the Negroes. During the past twenty years a widespread and well managed propaganda has been made to arouse the Negroes of the South, especially the rural population, to educate their children. In public mass meetings and conferences, in pulpits, in pamphlets and in the Negro press, in season and out of season, the importance of educating their children has been thoroughly impressed upon them. They have sought the facilities with which to do it. In most sections of the South these are very inadequate.

The large body of facts presented in the Report on Negro Education by Thomas Jesse Jones, issued recently by the United States Bureau of Education, leaves no doubt about the meager educational provision for these millions. This report says: “Public schools for Negroes have shared comparatively little in the educational advance that has taken place in the southern states during the past 15 years. … Teachers’ salaries for each child 6 to 14 years of age range from $15.78 to $36.50 for all pupils in the northern and western states represented in this table [p. 23, Vol. I of the report], and from $5.27 to $13.79 for white pupils and from $1.44 to $8.53 for colored pupils in the southern states here listed. It is important to note in studying these figures that the South is maintaining a double system of schools on finances limited both by the poverty of rural conditions and by an ineffective system of taxation.” Improvements have been made through cooperation of the state departments of education and the General Education Board in the maintenance of state supervisors of Negro schools, and through the work of the Jeanes Rural School Fund, the Slater Fund and the Rosenwald rural school building activities. But these improvements have necessarily touched as yet only a limited number of places; they take time, and the masses of the Negroes know of them only here and there. They think of the miserable schools they see and hear much of magnificent provisions in the North.

After all this movement of the southern Negro population someone asks, What is going to be the outcome? What is going to be done in the South? The South has seen the Negro laborer in a new light and is setting a new value upon his labor. Wages have been raised in many parts. The increase in many sections has been small. It has not kept pace in most cases with the high cost of living; but wages have been raised. Many plantation owners are reported as having expressed their intention of making and as having taken steps to make some improvement in their methods of dealing with tenants. The touching of the pocket nerve is calling forth response. The sense of justice and fair play is asserting itself also among the liberal and enlightened white citizens. Negroes in many localities agree that the treatment received at the hands of white people has improved.

A most significant thing in this connection is the effect of the liberal, fair dealing and good treatment of some employers preceding the present migration. Case after case of such employers has come to the writer’s knowledge. They have not suffered so seriously from loss of employees as have others in the same locality. For example, some employers in the Birmingham industrial district and some in the Virginia tidewater have suffered comparatively little from loss of laborers. The wages of these firms have been reasonably advanced from time to time; and a policy of fair, liberal treatment from bosses and superintendents has been the rule for years. Planters in Georgia and Mississippi of the same liberal type have had similar experience.

Practically every southern state has attempted to stop the migration by laws against labor agents. Many of the states already had laws to regulate or prohibit the exodus of laborers through the activity of labor agents. Some of these were revised and new ones passed.2 The laws have usually taken two forms: excessive labor agents’ license or requirements of residence. One state law passed in 1917 has a unique provision which requires the agent or agents to make surety that each laborer removed from the state shall not return as a charity charge.

School authorities are gradually awaking to the need of better school provision. One member of a county school board said, “We propose to improve the Negro schools in the same proportion and manner as the white schools.” The strongest public statement at a national conference on Negro education held under the auspices of the Bureau of Education last August was an expression for justice to Negroes in public education which was made by the state superintendent of education of Louisiana. This state has very large illiteracy among Negroes.

Perhaps the two most far-reaching and encouraging accompaniments of the migration movement are the beginning of frankness and plainness of speech by the leading white southern newspapers and of southern white men and women, and the open conferences and frank conversations between the thinking men and women of both races in the South. A summary of interviews had by several persons with editors of thirty-one leading newspapers in eighteen cities of eight southern states shows that nearly all of these editors are in sympathy with liberal views of democratic justice for Negroes. Many of these editors have embraced the times and have given expression to views quite in advance of the conventional opinions of their communities. The high-water mark has been touched by a number of them.

Commenting on the Houston riots, the Memphis Commercial-Appeal said: “The peace depends upon the conduct and intelligence of the white people. … We have the big advantage of education, and we have other advantages. Therefore the duty rests upon white people to see that there is peace and order.” The Richmond Times-Dispatch said: “The South needs the Negro, and to keep him must be just to him.” The Nashville Tennessean and American in an editorial on Negro migration said: “Then, having made higher wages the main material of our dam, we must throw in a rip-rap of better treatment. Something ought to be done about better housing conditions. … But bullying, bulldozing and blustering on the part of officers will have to stop. The officer who manhandles or mistreats a Negro who is behaving himself is not worth nearly as much to the community as the Negro. … The Negro is not to be blamed for going. The North is not to be blamed for asking him to go. … All the blame falls upon the southern people, who permit conditions that will allow the Negro to be lured away.” In an editorial against mob violence, the Nashville Banner said: “It is not the Negro’s fault that he is here. … He is a native of this soil as much as the whites. He is a human being and he is entitled to full recognition of his living rights and his humanity. He is in many ways exceedingly useful. The South needs 121 his labor and prefers it to any other. There is serious objection to his emigration, and without any regard to his social and political status, he is entitled to humane treatment and the full protection of the law. Anything else reflects on white people and works to their detriment more than it does to that of the Negro.” Commenting on a sermon on suppression of lynching, the Atlanta Constitution said: “In mob violence and the spirit of the mob there is nothing that a law-abiding citizen can condone; nor that is not repulsive and abhorrent. If we are going to have mob rule, we may as well abolish our courts. But we are not going to abolish our courts, and therefore we have got to abolish the mob.”

Gradually the silence of the liberal South is being broken. The conscience of this class is speaking its highest convictions. No less important than press utterances have been the statements of white southerners in public addresses and public gatherings. Two notable utterances were voiced the summer of 1917 at the Law and Order Conference of White Southerners held at Blue Ridge, N. C., and in the meeting of the University Commission on Southern Race Questions in Washington, D. C. In the letter mentioned in a preceding paragraph the University Race Commission said: “The South

cannot compete on a financial basis with other sections of the country for the labor of the Negro, but the South can easily keep her Negroes against all allurements if she will give them a large measure of those things that human beings hold dearer than material goods.” The Blue Ridge Conference said in a resolution: “We pledge to each other and to the people of both white and black races in the South our utmost endeavors to allay hurtful race prejudice, to promote mutual understanding, sympathy and good-will, to procure economic justice, and in particular to condemn and oppose all forms of mob violence.”

Recent lynchings in Tennessee have led not only to vigorous protests from the white press, pulpit and individuals, but has resulted in the formation of a Law and Order League for the suppression of mob violence. (Reported in the Survey of March 16.) Starting in a local organization at Nashville and composed of the leading business and professional men, the movement in less than a month has drawn white men from all over the state. Representatives of thirty-three cities, towns and counties of the state met and formed a statewide organization. They propose to create a public opinion by means of literature, lectures and the press and to secure enforcement of existing laws and the enactment, of new ones by all lawful meanfc to stop these outrages. Their proclamation rings with conviction and decision for action. One sentence shows its quality: “We have a strong conviction that lynching is unjustifiable under any and all circumstances, and is wrong in the sight of man and in the sight of God.”

Reports of many private conversations and conferences of white and colored citizens show that many white people with open minds are talking with Negroes and inquiring what may be done to accord what they now agree is simple justice to Negroes. Many of the Negro spokesmen are saying frankly what they believe to be the mind of the group and what they want as a just share of democratic advantages of wages, hours and conditions of work, schools and protection of “life, liberty, property and the pursuit of happiness.” One report from Alabama stated that, at a conference, a Negro farmer in trying to express the desires of his people said to the leading white banker who was presiding, “And, sir, we, we wants the ballot fer to help say who governs us.” When the banker replied that the good citizens of the state proposed to see that their desires were met, the Negroes present rose in a body and applauded loudly.

Perhaps in these stirring days when “the old order changeth, giving place to new,” no other one thing has made more for the improvement of race relations in the South than the readiness with which Negroes have responded to the national draft law. Southern newspapers have said they responded more readily than the whites in many localities. To the rank and file of Negroes the present world war means a war for freedom. They see in it a promise of greater freedom for all weaker peoples, themselves included. The departure of the drafted colored men has given evidence of the newer cordial relations between the races that is developing. Many localities have made the departure of the Negro conscripts a festal day. In Birmingham and in Mobile, Ala., the leading citizens took charge of the ceremonies, and the Confederate veterans headed the procession of Negro recruits as they marched to the railroad station to entrain.

122 The sequel of the migration, then, is bearing fruit by making for better wages, better treatment of Negro laborers, a more liberal expression of opinion from the southern press and from white leaders a freer exchange of views between the white and Negro leaders and action for law and order. These changes will surely bring greater amity and contentment to the South, white and black, and thus make, migration unnecessary.

In closing an account of the southern part of this important movement, one may venture to propose a few constructive plans:

White and Negro citizens have formed organizations to carry on such activities in both rural districts and urban centers in several parts of the South. These examples demonstrate that such a plan will work. It will speed up the progressive changes taking place in the South. It will increase the number of southern white persons who believe in fair play for the Negro and will stimulate public opinion in the same direction. It will tend to satisfy the Negroes of the South by removing the causes for their departure. It will help toward that democratic adjustment of race relations so essential to the future of the nation and so vital to the future of civilization.

See discussion by the writer in The Negro at Work in New York City, Columbia University Studies in History, Economics and Public Law. Vol. XLIX. No. 3; Also Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Vol. 49, Sept. 1917.↩︎

See twenty-second Annual Report of the Commissioner of Labor, Labor Laws of the United States.↩︎