Address given at the First Sociological Club. Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries. mums312-b196-i035. ca. 1897.

1I desire this afternoon to read to the First Sociological Club a candid criticism of its’ work and a suggestion for its’ future activity. I do this the more boldly because I am a member of the organization and as such must bear my part of the responsibility for its’ short comings; and at the same time, I speak as an outsider, for in the year that I have had my name on the rolls I have had no opportunity to share in the work of the club. I always hear with a certain foreboding shiver of the formation of a club for any kind of sociological work, for my experience has taught me that the percentage of absolute failure among such clubs is very large. The trouble is apt to be that the persons forming clubs for social reform have very vague ideas of what the science of sociology really is, and what is the real aim and object of their striving. Consequently it can easily happen that they drift aimlessly on until the members begin to wonder whether it is worthwhile to waste so much time doing nothing. I fancy I have seen in this club something of the same tendency, and it seems to me that the great need of this organization is a clearer conception of its’ aims and more practical and persistent work to accomplish these objects.

I have therefore chosen for my subject A Program for a Sociological Society, and I want to divide what I have to say in six parts. First I want to show what Sociology is. Second— What the science has accomplished. Third— By what methods its work has been done. Fourth— How the material and knowledge thus collected can best be utilized. Fifth— What the society has already accomplished and why, And finally what this society might and ought to do.

There was a vast revolution which took place in the early part of2 this century that is too often forgotten by educated people. It came after that terrible upheaval of human institutions which we call the French Revolution, after the orgies of Robespierre, Danton, and Marat, and became finally the great instrument that freed Europe from the grasp of the arch-tyrant Napoleon. This revolution was the industrial revolution of the 19th century. It began in the 18th century, when the science of chemistry was first well established, when geology gained a sure foundation when Brinley showed the world how to dig canals uphill, when iron began to be smelted by coal instead of charcoal, and above all when James Watt turned a tea-kettle into a steam engine. Such epoch-making inventions changed the civilization of the world and with the dawn of the 19th century came an industrial revolution — factories started up, towns grew, commerce expanded, capital increased, the world market widened. If we regard this industrial movement more carefully we shall see that of all departments of human industry the manufacture of cotton made the most gigantic strides in this epoch. The ancient world dressed in wool, the middle age in wood and linen, the modern world dressed largely in cotton. The series of inventions that made cotton manufacture possible are a curious example of coincidence. Between the years 1775 and 1825, Arkwright Hargreaves, Cartwright, and Eli Whitney had changed the spinning wheel into the factory and made the southern United States the cotton field of the world.

This industrial revolution had serious consequences: first it fastened American Slavery in this country and made emancipation more difficult, and the Negro problem more baffling; More that that in all lands it gave rise to and intensified those intricate questions of life and death and civilization which we call social problems: human being were, by the new concentration of industrys, crowded into centers of population and the difficulties, diseases, and maladjustments of human life became intensified and more patent to the eye. Crime, poverty, disease, pros3titution, ignorance, and death began to assume threatening proportions. Men came to be attracted to these sinister phenomena and to ask what they really meant, how far they were remediable, and how far inevitable.

There was then but one science which undertook the study of the phenomena of human action and that was the science of political economy. But this science was limited in scope: it began in the 17th and 18th century when the phenomena of money and international trade first assumed importance and confined itself simply to a study of wealth: it asked how goods were produced, how they were distributed among the producers, and how their owners exchanged them for other goods. It thus took into account only a few human activities under stable conditions of society. The industrial revolution, however, had greatly changed conditions, and brought a distinct demand for wider inquiry into the causes and scope of human action — deeper search for the reasons of present conditions and the intelligent application of such knowledge to methods of social regeneration. This was the beginning of the modern science of Sociology.

Sociology is therefore the name given to that vast field of inquiry into human action as manifested in modern organized life. It cannot study all human action under all circumstances, but that human action which by its regularity gives evidence of the presence of laws. What these laws are we hardly know, and yet we do know that there are in life curious and noticeable coincidences — rhythm in life and death, a working out of cause and effect, evidences of force action and reaction, which cannot be ignored or neglected. Many eminent men still insist that this mass of partially digested facts cannot be called a science — and indeed if you mean by science, a body knowledge with definitely stated laws, and carefully systematized facts, then Sociology is not yet a science and may never become one. But if you mean by Sociology a vast and fruitful field of inquiry into the mysterious phenomena of human action, which has yielded evidence of the working of scientific laws to some extent, and promises much for the future — if such a work deserves, as many4 think, the name of science, then Sociology is one of the greatest of sciences.

But it is impossible to tell what a science is merely by defining it — the definition is the last thing a science discovers — indeed it can truthfully be said that no science can be fully defined until it is perfect, until its work is done. The best explanation of a science then is a description of the sort of work it is doing and what it has already accomplished. I come therefore to the second point in my talk.

Sociology has studied the proportionate number of the two sexes in the different countries, the number of people of different ages, the number of births each year in different localities, the number of deaths from various diseases, the size of families, the average number of rooms in dwellings, the extent of illiteracy, the number of communicants in the different churches the occupations which men pursue, the income from their work, the way that income is expended; the number of the blind, deaf, dumb, and insane, the extent and degree of poverty, the prevalence of suicide, the extent and kinds of crime, the characteristics of criminals, the distribution and migration of population, the distribution of property, etc. Moreover it has sought to generalize much of this mass of facts and show how all these actions and phenomenas tend to a certain rhythm and regularity which we call the social group. In the social group the distribution of the sex and age of the individuals remain continually about the same despite birth and death, and the rate of births and deaths varies so little that it can be predicted within limits. The income, occupation, expenditure, and crime tends in the same way under forms of law. This so-called Social Law seems partly voluntary, partly involuntary, but in all cases its regularity is much greater than the casual reader dreams. These social groups in turn combine to form that higher generalization which we call Society. Society is simply a general name for the regularities of human action — for the general fact that when 50, 100, or 1,000,000 live together they do not all act irresponsibly or at random but according to well-known5 maxims, social forces and laws.

All this that I have said can best be illustrated by a few actual examples. In Europe, for instance, repeated investigation has proven that for every 1,000 males there are about 1,024 females. This is Characteristic of old countries. In the United States, on the other hand there are only 952 females for every 1,000 males. In the older, eastern states, however, we should expect to find conditions approaching those in Europe — and sure enough there are 1,005 females to every 1,000 males. To show the significance of such facts let us go a step farther: We find in the city of Baltimore 1,310 Negro women to every 1,000 men. We can immediately say this is surely an abnormal situation and must have something to do with the large number of illegitimate births in that city.

Statistics of age show that in normal countries about one third of the population is under 15 years of age, yet the nations vary considerably: for instance take children under 10 years of age; in England they form 24% of the population, in France only 18%, among the Negroes of the land 28%. Turning now to the old people 60 and over and we find that they form 7% of the population of England; 13% of that of France; and 2% among our race. Such differences simply mean poor family life among our people.

The statistics of births and deaths are always of great interest and consequently liable to misuse. We may have two especially marked types: a population with a low birth-rate and low death-rate like France or a population with a high birth rate and high death rate like American Negro. The latter is a sign of a low standard of culture — early marriage, illegitimacy and neglect of the laws of health; the former is usually a sign of high civilization — postponement of marriage until the support of a family is assured, and life according to the laws of hygiene. Son in the same country the character of a community may easily be approximately fixed by measuring the number 6 of people in every thousand that die annually. A death rate above 26 is high, while one above 30 points to grave dangers. The rate may be as low as 18 as in Norway. The average death rate of Negroes in cities is 34.

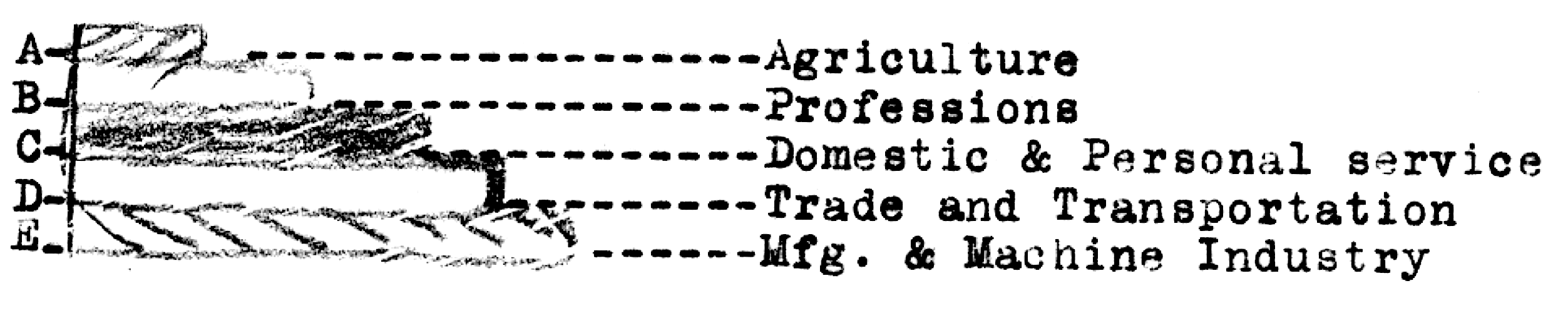

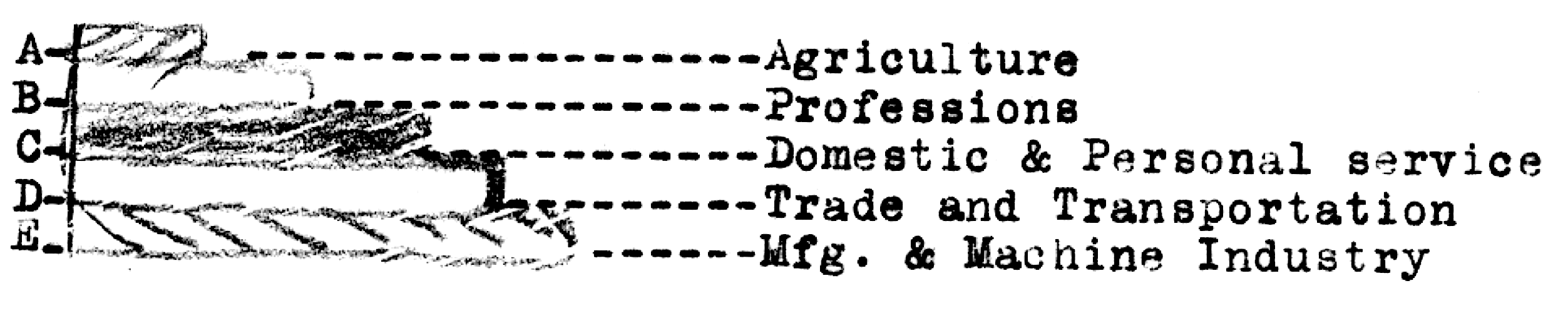

Where sociological inquiry reveals great differences in the conditions of different groups of people this is usually evidence of some unseen cause which makes the variation. For instance, we can represent the occupations of the people of Philadelphia by the following set of door steps:

If however we represent the occupations of the Negroes of the city, we find the steps hard for climbing.

What is the meaning of this striking difference? It is explained fully by one comprehensive word SLAVERY. Thus history writes itself in figures and diagrams.

In the matter of crime, sociology has done some of its best work; let us notice only one — the connection of crime and age. In Germany for instance it has been found that 15% of all persons between 21 and 40 have been convicted for crime, 9% of those between 40 and 60, and 7% of those between 12 and 18 years of age. Further analyzing these figures it is found that the most criminal age is between 20 and 30, and among young unmarried men. Taking for instance the Negro criminal in the Eastern section of Pennsylvania; we find the remarkable fact that 67% of them were under 30 years of age and 11% under 20.

Using such minute and detailed statistics sociology has built up the theory of the social group. The country village is a social group. 7 Its population distributed in a certain normal order as to age and sex and conjugal condition. Its birth and death regulating the increase of population. There is some crime, a school, a church, a village store. The population is divided among different occupations, social classes make a faint appearance and there is a general public opinion which represents of synthesis of like ideas. Such a group may grow to a city or to a nation, but as it grows we note certain peculiarities: it forms within itself other smaller groups for special purposes — clubs for amusement or reading, church societies, associations of capital and labor called shops or companies or factories and etc. These sub-groups we might call organs for carrying out the special work of society, just as the tissues of the body form here a heart and here an eye to serve the whole organism of the body. This we refer to when we speak of society being organized — of course this is but an analogy for the organization of society is far from complete and individual free will must ever hinder that consummation in this world. Nevertheless advance in civilization is to a certain extent advance in the perfecting of the organization of society.

Such is the work that Sociology has accomplished. It is to be sure only a beginning: our statistics are woefully imperfect. Our methods of observation are crude and the material at hand is largely an unclassified mass of facts, the value of which is various and uncertain. Nevertheless gigantic strides have been taken in the last 10 years, something has been done, and the outlook for the future is bright. This brings me to the fourth point I wish to discuss.

The interest in social reform and general betterment which animates so many excellent people today must not be mistaken for the science of Sociology. There are many people who have a vague desire to right wrongs, help the needy, and reform the vicious. Unfortunately these people in 8 very many instances are ignorant of the results of scientific research in these lines — they do not know the value and meaning of statistics and they often waste money and energy, or do absolute harm, either by antiquated or discredited methods. If anyone should inform an ordinary citizen that chemists had discovered a new element, Argon — he would say very well or bravo I and be done — he would not attempt to discuss the matter or draw conclusions — he is no chemist and does not attempt to be. If he wishes to use the results of chemical research he seeks the advice of a chemist. In the realm of sociology, however, the case is very different: tell a man that the death rate of the Negroes is 36, and immediately he is ready to discuss the matter, write articles, form clubs, and spend money although he knows that he is not an expert in statistics or a student of sociology. What ought to happen in this case is clear: the man ought to say candidly that he knows nothing about death rates — is 36 high or low or medium? What has been the history of the variation of death rates? How do the death rates of different peoples compare with this? A sensible man ought to ask: What does a death rate of 36 mean: what in the light of the expert statistical knowledge and the careful sociological research of the last quarter century, is the proper interpretation of this figure 36, which otherwise is to me a Sphinx and an enigma.

The civilized and thinking part of the modern world is gradually and surely coming to this position. The first thing people ask of social reformers now in not how earnest are you or how great is the need of reform but rather what do you know about the actual situation and how does the best of expert opinion interpret these facts. Men recognize the fact that such expert opinion may err but they are coming to see that the occasional error of men who give their life to knowing is not as dangerous as the perpetual error of men who guess or dogmatize. The facts and the meaning of the facts are then the first steps in modern social reform.

9 How now shall the mass of intelligent people who have not time to be experts put themselves in position to use the material collected by sociologists in the practical work of reform? We can best answer this by seeing the work done in reform during this century.

One of the first movements was the English Abolition of the slave-trade: for this the House of Commons collected a mass of statistics — the number of ships engaged, the amount of capital invested, the methods employed to capture slaves, the routes of sailing, the number transported, the death rate among slaves and sailors, and etc. They sought the history of the subject, the general conditions, the opinions of exports statisticians and when they began to legislate on the subject they knew what they were doing and no nation had done so much to stop Negro slavery as these same Englishmen who studied the matter so thoroughly.

Again take the matter of prison reform. When the question was first agitated there wasn’t a crank in England or America that hadn’t an opinion and a panacea — It was do this, do that, make their punishment as severe as that of galley slaves; treat them as unfortunate victims of society; make their work hard, let them lie idle; hang them, give them tracts to read, and etc. Society has outgrown this: gradually here and there we have collected facts — not how someone thinks a plan might work but how the plan actually did work when it was tried; we have studied criminals instead of taking it for granted that we know them, we have watched crime instead of theorizing about it and then with the material we have tried careful experiments — experiments in housing prisoners, experiments in punishment, experiments in work and diet; until today no intelligent man thinks of aimlessly giving advice as to crime — he knows that this is a subject for experts — a subject still dark, with much to be learned, but still a realm where the day of guesswork is past. In the matter of charity, perhaps the greatest advance has been made. The classic examples of this is the history of the English poor law. At first England frowned fiercely on beggery and poverty and whipped and 10 branded and hanged the poor devils. Then she melted into sentiment and coddled and stuffed her paupers until it seemed ae though all England would go to begging. Finally the state bethought itself to ask who are the paupers, what makes pauperism, how can we decrease it and help people to help themselves? For this reason it now uses the statistics, studies social conditions, organizes charitable societies, avoids duplications of work, detects importers and seeks in every way to know the causes of poverty and apply intelligent and scientific remedies. The world is still far from solving the problem but we are much nearer than men were in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Thus sociological material is today used by all kinds of social reforms: the organizers of childrens societies,and of schools; those who seed to help the deaf and the blind, those who want to get work for the idle; saving banks and building associations are established on carefully ascertained principles, model homes built for tenants — indeed this is the age when lasting and effective reform has become systematic and scientific and has replaced sentiment and theory.

The question now comes:

I want to be perfectly frank in this matter and to say plainly that in my opinion this society has done nothing. I know we have organized — we have held meetings. We have had pleasant social gatherings and we have talked. But of actual work accomplished either in the line of knowing just what there is to be done, and just how we are to do it, and what there is to be learned as to method from the sociological work of the day, and above all of actual accomplished work, it seems to me perfectly fair to say that this society has done little more than nothing. Indeed I have several times seriously asked myself whether I was justified in attending those meetings and whether there was a reasonable prospect of an end of aimless talking and a beginning of definite doing. We seem to me in the first place to have no clear idea of what the society is for; 11 we seem again to have a tendency to fritter away precious time on trifles, we seen to forget when we are discussing ways and means that all this is not mere theory but that definite information of the experience of others in the work and of the general state of scientific knowledge on most of these points is easily obtainable. And finally we seem in the laying out of our definite practical work for committee to have not the faintest shade of an idea of the enormous difficulties and infinite complications of some of the subject we undertake. To particularities, at the last meeting the subject for discussion was the influence of tenement life on small children — a subject of the deepest importance and of wide influence There is a perfect mass of material on the subject — studies, maps and plans, vital statistics, satieties of dwellings and occupations, measurements of children’s bodies, experiments as to mental aptitude, inquiries into home life — indeed I could without difficulty gather right here in Atlanta a hundred volumes of material on the point to be discussed. If a sociological society had been going to discuss that subject what would one reasonably expect the trend of the discussion to be?

They would expect first that the general conditions of slums would be explained: Both maps of London would be exhibited and studies shown of the physical environments; the Hull House maps and papers would have been taken next; something would have been said of the slums of New York and Philadelphia. Then the general question of children would be approached — what physical surroundings are necessary and the lack of these would be illustrated by the death rate of children in slums; the moral demands of child life would be touched upon and criminal statistics produced to show how youthful criminals are bred in the slums; finally we would have the evil social effects — lewd talk, illegitimate children, prostitution, personal uncleaness, the spread of disease and the like. Those are some very elementary matters connected with the life of children in slums which any consideration of the subject must take up. But beside this the central part of the discussion ought to have been the slums of Atlanta: we 12 ought to have had the map of several typical alleys showing the size and relation of the houses, the number of rooms, the number dwelling there, and the number and size of children; the general characteristics of the families, the ability of the children in school or at work, the number of deaths in the alley in a year, the kinds of diseases, and a general history of the alley. From one to five such studies might have been made.

Such is what we might reasonably expect in the discussion of this subject by a club which calls itself sociological. And yet I doubt if any member of this society went from that discussion with a single new fact or idea. Nobody had studied the subject, nobody knew anything about the matter, no one had any information to impart. About two days before the meeting in the midst of a busy week’s work I was informed that I was expected to discuss a subject which experts have been studying 10 to 20 years. And when out of sheer respect for the intelligence of these members I mildly protested that two days was not enough time for such a subject — the society blandly waved its hand, and said “why you had three days”.

I remember last year at the Altanta Conference, the president of this society gave an outline of this organization and a list of its committees. I must confess it made a splendid showing: but there was one fact that the president omitted to mention and that was that very few of those committees had done any work worth mentioning. Nor was this the fault of the president: he had urged the society again and again to do actual work and the society did attempt to help the Atlanta Conference, but of all the bad reports that came into that conference that of this clubs was the worst. If it had not been for the personal work of Dr. Butler and Mr. Matthews the Atlanta Conference would have had to omit Atlanta from the cities investigated. I said to myself, however, this society is young yet — next fall the work will begin. And lo! at the first meeting I attended the club was adopting a new constitution. I must say I was somewhat disgusted — what do we want I thought of a New Constitution when we have done nothing 13 under the old one. A constitution is not worth the paper it is written on unless it is backed by deeds and give the deeds and I care not whether we have a constitution or not. One of the objects of the new constitution was said to be the facilitating of the organizing of other sociological clubs in other cities. I would as soon think of my baby advertising to teach persons to walk - why he can’t walk himself.

After the new constitution was adopted the same difficulties appeared as last year in the apportioning of work to committees. One afternoon last year we casually discussed the matter of crime. In a moment the discussion sped - we swept through the calendar of crimes in 15 minutes and attacked the subject of criminals; pausing there a moment we sailed rally to the matter of punishment, then to slums and education, then to the conduct of courts, then to color discrimination, then to the situation of the south and to the Negro problems. A library of 10,000 volumes would not have covered the matters we lightly discussed in that afternoon and then as I was opening my eyes in wonder, we suddenly appointed a committee and charged it with the whole matter. Does anyone wonder that we haven’t heard from that committee since? It is my candid opinion that if we had appointed a committee of 100 persons and given several thousand dollars to expend they could not possibly have accomplished the work we gave them in less than 300 years.

The trouble is we despise the day of little things — we neglect little movements, small efforts, tentative experiments, and throw ourselves blindly against adamantive walls which have withstood the assaults of philanthropists for centuries, we had a simple program of work laid before us; it was suggested that we make a careful map of the Negro slums of Atlanta and see how they were situated with regard to the various agencies for good. This was not theory or experiment — it was simply analogous to a great work now being done in New York City. Yet this society virtually spoiled the plan by appointing an aimless committee to give pastors of var14ious churches advice as to their mission fields in the city. The chairman of the committee protested at the time that this method of attacking the matter would not do — but not we must have the committee. And of course the committee never reported for it had nothing to report, several times other promising definite proposals for small beginnings have been made but no sooner were they launched then someone proposed something else, another pointed out that this method would not reform everybody and made the sunshine 24 hours in the day and the whole plan became amended and blocked and died a peaceful death in committees.

To sum up then: we as a society are not sure what we ought to do; and we have made clumsy and ineffectual attempts to do a mass of things without a knowledge of the facts or of the well-grounded theory of the subject. We add to our membership in a haphazard way, forcing people to join who simply come to visit; we appoint committees and distribute work in a way equally accidental and thoughtless and above all we yield to the temptation to talk and discuss when we have nothing to say.

But enough of criticism. I know it is much easier to find fault then to avoid fault — to pick flaws in work done than to do work. And yet candid criticism has its place — it lies at the root of all reform and after all in this devious world perhaps the wonder is that we stray so little rather than that we err so much.

Let me therefore turn to the last point I wish to consider.

The aim of a society of this kind ought to be to furnish accurate information to such agencies as are engaged in the work of social reform, to endeavor to increase the cooperation between those agencies, and to seek to establish new agencies for reform in neglected and unknown fields of effort. Let me take up these 2 things in order:

First, I say, this society should aim to gather facts and information for its own and others use. I was once pursuing an elaborate piece of investigation in regard to the negroes of a certain city, when I came across 15 a woman who could if she would give me much valuable matter, she looked at me suspiciously and said, “What’s the object of this investigation?” “simply to get at the truth”, I answered. “Do you propose to do anything after you get the facts”, said she. “We simply collect the facts”, I returned, “Others may use them as they will” Then you are trying only to get facts and not to better things”, she said. “Yes”, I again answered. “Humph, she replied and I’m still waiting for that information. Now this illustrates well the attitude of many minds toward careful and systematic collection of minute facts. Men are so filled with ideas of reform that they haven’t time to study the abuses which they seek to abolish and baldly assume that they know all about them. One of the most baffling things about the Negro problem today is the fact that so many people in this country are absolutely convinced that they thoroughly understand it. Especially is every Negro supposed to be born with a thorough understanding of this intricate problem in all its bearings. And yet a moment’s thought will convince us all of our ignorance. How many of us hear really know very much of the history and present condition of the eight millions of our race in this land? We call the”negro problem” certain bits of personal experience, joined to some ready and general information and to a good deal of gossip. There is not one of us that does not need to study thoroughly and minutely any part of this subject which we propose to work upon. This society should be a center for gathering such information in Atlanta, we ought to begin to study thoroughly, comprehensively, and minutely the situation of the Negroes of this city — we ought to become a bureau of accurate information for all facts connected with the Negro — wealth and poverty, business and labor, crime and pauperism, charity and reform, homes and streets, migration, wages, occupations, marriage and divorce, illegitimacy, education, church organizations, other organizations - every general fact which bears upon the condition of the Negro in this city, past and present ought to be carefully collected and recorded, and now and then published. 16 We should follow th« history of alleys, compile a careful list of the worthy, study minutely the abode and history of the criminals, keep an eye upon orphans and homeless waifs — in fact, no fact or condition should escape the eye and pen of a society whose chief desire it is to know the social problems they seek to solve.

For this work we should have committees, and every member of the organization be a member of some committee. Each committee should work under a chairman and the chairman could if he saw fit appoint sub-committees. At every meeting it should be the work of each committee to report some carefully ascertained facts to this committee and to report in writing not orally. The facts may be small or unimportant, they may be a study of a whole district, they may be historic data, illustrative incidents, but always accurate, always reliable and always designed to teach us more of the actual situation of the people and guide our feet in matters of reform.

These committee should be standing committees and no other committee ought to be appointed during the year, save in very exceptional cases. The committees should be appointed on such subjects as Poverty. Crime, Health, Homes, Churches, Education, Occupations, the defective classes, Wealth, Reading, and etc. — That is, simple comprehensive fields where much may be learned.

Second, we should endeavor to increase cooperation among the various agencies for social betterment among the Negroes of Atlanta: these agencies are the churches, the schools, the secret and insurance societies, and the benevolent efforts of various kinds. Our object here should be not to meddle, not to interfere in the work of others, but by spreading information and pointing out fields of action we should seek to reduce the duplication of benevolent work to a minimum and get the widest good fellowship and cooperation possible. Mother’s meeting, lectures, circulating libraries, savings associations and general reform work could in this way be spread by sheer contagion through the various church constituencies and communities.

This society should stand ready to send to ever single church in Atlanta 17 two, three times a year competent persons to explain to the members some elementary matter of reform — ventilation, the use of water, sewing schools, hygienic cooking, reading, saving, and etc. in this way effort could be stimulated in existing agencies toward betterment of present conditions.

For this purpose there should be an executive committee under the chairmanship of the president which should arrange meetings and conferences, and tell us what other movements are doing and seek to build gradually a central board which would federate all the benevolent efforts of the city among Negroes and cooperate with similar efforts among whites.

Thirdly the society should endeavor to find out and explore fields of reformatory effort neglected by other agencies, or forgotten or unknown. And should seek here to inaugurate new movements for betterment. In this work however great care must be exercised. Our committees stand for ears open to all sounds from everywhere and letting no whisper escape. But our efforts at actual reform must not be thus dispersed. We cannot reform the whole world at one, we must concentrate our efforts; one thing at a time and that a small thing; careful tentative effort, feeling our way slowly, making no failures and takin no backward steps and above all remembering that permanent reform is slow work and that 10 years in such work is a mere bagatelle. One thing at a time then and let that one thing take our whole strength. We might for instance do this: each of us here might contribute to the committee on schools a book suitable for children to read. We each might get a few friends to give similar books. Then this modest little library of say 25 or 30 volumes properly labelled and cased might be place in one of the public schools to circulate for a month. Then in another school for a month, then in another, next year we might collect another small library — in 10 years we might thus place in every school house in the city a circulating library and begin to send some to the country schools — simple work, nothing great, no wholesale manufacture of saints, nothing to wave our hands about or yell, but Work, Reform and Advance such as in the past has built nations and 18 and empires. When this enterprise was well started and in charge of the proper committee — or possibly given over to some special organization, we could begin another and larger effort — but slowly, carefully. We could start a movement toward a penny savings bank. Not a money making institution, but a benevolent enterprise to encourage thrift run on business principles. We could select in the city three or four Negroes whose reputation for honesty and profity was unquestioned. If possible we would ask three or four interested white men to act with them and form the directory board of a Negro Penny Savings bank. Each church could be induced to hold meetings and hear talks on thrift and little things. The various schools — Spelman, Atlanta Baptist, Clark, Morris Brown and others could preach a crusade of saving at chapel exercises. At several of the larger colored stores, a small stand, a tin box, and a padlock could be placed and a member of the committee on saving could be placed there from 8 to 10 P.M. on Wednesday and Saturday night. Bankbooks with stamped receipts could be given out. Ihe enterprise would flourish for a while then it would die down, but we would not die down — more lectures, more talks, tracts, and posters, a notice in the Constitution and habits of saving would begin to grow and we would gradually know where to place our branches — how to encourage people. In five years we might have $200 or $300 in deposits; in 10 years $2–3000. In 15 years we might hire modest quarters, use our money for a building association or surrender the whole work to a special society, nothing great in such a movement — nothing to take ones breath away — it has been done a hundred times in other cities among other people and in a few cases among Negroes — but this true rising — which does not necessarily call for a constitution on paper but it calls for a certain mental and moral constitution in us which is too often lacking.

I might easily go on naming a hundred different methods of work distributing tracts, offering prizes in the schools and churches, a comprehensive system of neighborhood visiting, careful organized and persistently 19 conducted serine of mothers meetings and fireside schools, temporary care of waifs and foundlings, shelters for friendless girls, a social settlement house in the slums, — all these and many more — not all at once, not all in a year, hut slowly, gradually, doggedly — such work lies before.

Finally as to our meetings we must stop throwing away time in endless, senseless and aimless talk. We are here for business, First we want information on local conditions from the chairman of committees and chairmen having nothing to report ought to be made to feel thoroughly ashamed for their neglect and carelessness. The reports should oe brief, definite, and contain actual data. We do not want essays on what ought to be dona but what your committee actually has done and when it did it and how it did it and what the result was. We do not want vague general statement but definite, brief, concise records of date, place and deeds. After these reports and a short discussion of the meaning of these facts then we should turn to the work of the meeting: somebody who has studied something and knows about it and has his knowledge in a shape to impart clearly and somewhat more briefly than I am doing, should then take the floor and teach us something, either in sociological theory, or in efforts of other lands or cities, or in local conditions, we do not want general essays, or schoolboy papers — but facts and information and carefully weighed opinion. Then we can go knowing more than when we came and better prepared for work. If no one has such a paper prepared, then let us take one of the dozens of excellent works on social questions and reading it, passing it from hand to hand and discussing it. Our let us adopt a textbook and study the subject we profess to know something of.

If in a half-century we thus increase our knowledge of social conditions and start a few movements to better abuses then this club will deserve well of the nation.

Fellow-workers, the Negro problem is in this room — between these four walls and it is the question as to whether the best class of intelligent 20 Negroes can so cooperate in unselfish effort as to better in some degree the condition of the Negro masses. Among the masses we have problems but not Negro problems — there are problems of crime, of poverty, of sexual lewdness, of ill-health, of heredity. The Negro problem is the question whether those who have raised themselves above this dead level of degradation can do as other nations have done — cooperate, investigate, sacrifice, and lift as they climb.