Ebony and Topaz A Collectanea. Edited by Charles S. Johnson. 1927, pp. 144–147

—Old popular song

144 For many years it has been the custom of certain portions of the Negro group living in Southern cities to give some form of party when money was needed to supplement the family income. The purpose for giving such a party was never stated, but who cared whether the increment was used to pay the next installment on the “Stineway” piano, or the weekly rent? On the one hand, these parties were the life of many families of a low economic status who sought to confine their troubles with a little joy. On the other hand, they were a wild form of commercialized recreation in its primary stages. Humor was the counterpart of their irony.

No social standing was necessary to promote these affairs. Neither was one forced to have a long list of friends. All that the prospective host required to “throw” such an affair would be a good piano player and a few girls. Of course you paid an admission fee—usually ten cents—which was for the benefit of some Ladies Auxiliary—though it may have been an auxiliary to that particular house. The music invited you, and the female of the species urged that you remain. The neighborhood girls came unescorted, but seldom left alone. Dancing was the diversion and there is no reason to doubt that these affairs were properly named “SHIN-DIGS.”

There was “Beaver Slide,” that supposedly rough section of the Negro district, situated in the hollow between two typically Georgian Hills. Here lived a more naive group of Negroes whose sociables were certain to make the passers by take notice. The motto for their affairs seemed to be “Whosoever will let him come, and may the survived survive.” Twenty to thirty couples packed into two small rooms, “slow-dragging” to the plaintive blues of the piano player, whose music had a boss accompaniment furnished by his feet. The piano was opened top and front that the strains may be more distinct, and that the artist may have the joy of seeing as well as hearing his deft touches (often played by “ear”) reflected in the mechanics of the instrument. They were a free-“joy-unconfined” group. Their conventions were their own. If they wished to guffaw they did—if they wished to fight they did. But they chiefly danced— not with the aloofness of a modern giglio hut with fervor. What a picture they presented! Women in ginghams or cheap finery, men in peg top trousers, silk shirts, “loud” arm bands, and the ever present tan shoes with the “bull dog” toe. Feet stamped merrily—songs sung cheerily—No blues writer can ever record accurately the tones and words of those songs—they are to be heard and not written—bodies sweating, struggling in their effort to get the most of the dance; a drink of “lightning” to accelerate the enthusiasm—floors creaking and sagging—everybody happy.

145 During the dance as well as the intermission, you bought your refreshments. This was a vital part of the evening’s enjoyment. But what food you could get for a little money! Each place had its specialties—“Hoppinjohn,” (rice and black-eyed peas) or Mulatto rice (rice and tomatoes). Okra gumbo, Sweet potato pone—sometimes Chicken—Chitterlings—Hog maws—or other strictly southern dishes. You ate your fill. Dancing was resumed and continued until all were ready to leave—or it had suddenly ended in a brawl causing the “Black Maria” to take some to the station house and the police sending the remaining folk to their respective homes.

And there were those among us who had a reverential respect for such affairs. At that time there was no great popularity attached to a study of the Negro in his social environment. These were just plain folks having a good time. On the other hand, they were capable of description, and to those of us who knew, they were known as “struggles,” “break-downs,” “razor-drills,” “flop-wallies” and “chitterling parties.” These they were in fact as well as fancy. It was a struggle to dance in those crowded little rooms, while one never knew if the cheaply constructed flooring would collapse in the midst of its sagging and creaking. What assurance did one have that the glistening steel of a razor or “switch blade” would not flash before the evening’s play was done? And very often chitterlings were served—yet by the time forty sweating bodies had danced in a small parlor with one window—a summer’s evening—and continued to dance—well the party still deserved that name. But Mrs. Bailey paid her rent.

NEWS ITEM: “Growing out of economic stress, this form of nocturnal diversion has taken root in Harlem—that section known as the world’s largest Negro centre. Its correct and more dignified name is “Parlor Social ,” but in the language of the street, it is caustically referred to as a “house rent party.”

With the mass movement of Southern Negroes to Northern Cities, came their little custom. Harlem was astounded. Socially minded individuals claimed that the H.C.L. with the relative insufficiency of wages was entirely responsible for this ignominious situation; that the exorbitant rents paid by the Negro wage earners had given rise to the obnoxious “house rent party.” The truth seemed to be that the old-party of the South had attired itself a la Harlem. Within a few years the custom developed into a business venture whereby a tenant sought to pay a rent four, five and six times as great as was paid in the South. It developed by-products both legal and otherwise, hence it became extremely popular.

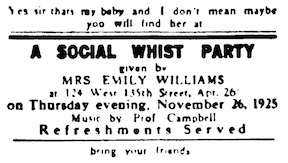

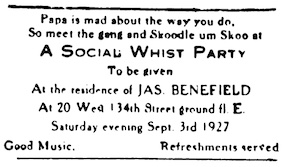

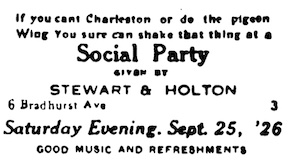

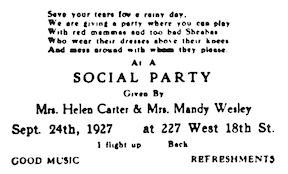

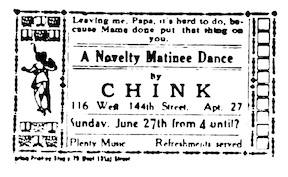

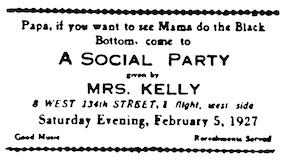

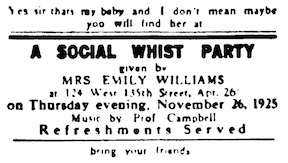

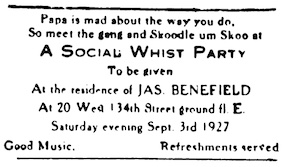

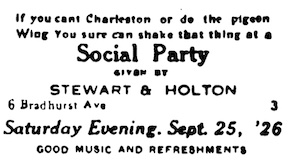

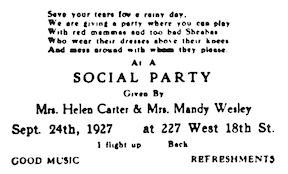

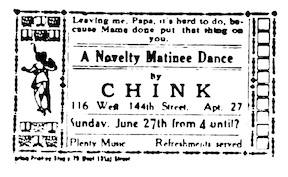

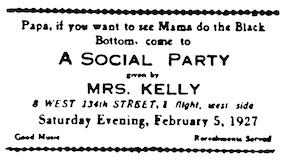

146 There has been an evolution in the éclat of the rent party since it has become “Harlemized.” The people have seen a new light, and are no longer wont to have it go unnamed. They called it a “Parlor Social.” That term, however, along with “Rent Party” is for the spoken word. “Social Whist Party” looks much better in print and has become the prevailing terminology. Nor is its name restricted to these. Others include “Social Party,” “Too Terrible Party,” “Too Bad Party,” “Matinee Party,” “Parlor Social,” “Whist Party,” and “Social Entertainment.” And, along with the change in nomenclature has come a change in technique. No longer does the entrepreneur depend upon the music to welcome his stranger guests; nor does he simply invite friends of the neighborhood. The rent party ticket now turns the trick.

There straggles along the cross-town streets of North Harlem a familiar figure. A middle aged white man, bent from his labor as the Wayside Printer, is pushing a little cart which has all of the equipment necessary for setting up the rent party ticket. The familiar tinkle of his bell in the late afternoon brings the representative of some family to his side. While you wait, he sets up your invitation with the bally-ho heading desired, and at a very reasonable price. The grammar and the English may be far from correct, but they meet all business requirements since they bring results. What work the Wayside Printer does not get goes to the nearest print shop; some of which specialize in these announcements.

A true specimen of the popular mind is expressed in these tickets. The heading may be an expression from a popular song, a slang phrase, a theatrical quip or “poetry.” A miscellaneous selection gives us the following: “Come and Get it Fixed;” “Leaving Me Papa, It’s Hard To Do Because Mama Done Put That Thing On You;” “If You Can’t Hold Your Man, Don’t Cry After He’s Gone, Just Find Another;” “Clap Your Hands Here Comes Charlie and He’s Bringing Your Dinah Too;” “Old Uncle Joe, the Jelly Roll King is Back in Town and is Shaking That Thing;” “Here I am Again. Who? Daddy Jelly Roll and His Jazz Hounds;” “It’s Too Bad Jim, But if You Want To Find a Sweet Georgia Brown, Come to the House of Mystery;” “You Don’t Get Nothing for Being an Angel Child, So you Might as Well Get Real Busy and Real Wild.”

And at various parties we find special features, among them being “Music by the Late Kidd Morgan;” “Music by Kid Professor, the Father of the Piano;” “Music by Blind Johnny;” “Music by Kid Lippy;” “Skinny At the Traps;” “Music Galore;” “Charge De Affairs Bessie and Estelle;” “Here You’ll Hear that Sweet Story That’s Never Been Told;” “Refreshments to Suit;” “Refreshments by ‘The Cheater’.” All of these present to the average rent party habitueé a very definite picture of what is to be expected, as the card is given to him on the street corner, or at the subway station.

The parties outdo their publicity. There is always more than has been announced on the public invitation. Though no mention was made of an admission fee, one usually pays from twenty-five to fifty cents for this privilege. The refreshments are not always refreshing, but are much the same as those served in parts of the South, with gin and day-old Scotch extra. The Father of the Piano lives up to his reputation as he accompanies a noisy trap drummer, or a select trio composed of fife, guitar, and saxophone.

Apart from the admission fee and the sale of food, and drinks, the general tenor of the party is about the same as one would find in a group of “intellectual liberals” having a good time. Let us look at one. We arrived a little early—about nine-thirty o’clock. The ten persons present, were dancing to the strains of the Cotton Club Orchestra via radio. The drayman was just bringing two dozen chairs from a nearby undertaker’s establishment, who rents them for such affairs. The hostess introduced herself, asked our names, and politely informed us that the “admittance fee” was thirty-five cents, which we paid. We were introduced to all, the hostess not remembering 147 a single name. Ere the formality was over, the musicians, a piano player, saxophonist, and drummer, had arrived and immediately the party took on life. We learned that the saxophone player had been in big time vaudeville; that he could make his instrument “cry;” that he had quit the stage to play for the parties because he wanted to stay in New York.

There were more men than women, so a poker game was started in the next room, with the woman who did not care to dance, dealing. The music quickened the dancers. They sang “Muddy Water, round my feet—ta-ta-ta-ta-ta-ta-ta.” One girl remarked—“Now this party’s getting right.” The hostess informed us of the menu for the evening—Pig feet and Chili—Sandwiches a la carte, and of course if you were thirsty, there was some “good stuff” available. Immediately, there was a rush to the kitchen, where the man of the house served your order.

For the first time we noticed a man who made himself conspicuous by his watchdog attitude toward all of us. He was the “Home Defense Officer,” a private detective who was there to forestall any outside interference, as well as prevent any losses on the inside on account of the activity of the “Clean-up Men.” There were two clean-up men there that night and the H.D.O. had to be particularly careful lest they walk away with two or three fur coats or some of the household furnishings. Sometimes these men would be getting the “lay” of the apartment for a subsequent visit.

There was nothing slow about this party. Perfect strangers at nine o’clock were boon companions at eleven. The bedroom had become the card room—a game of “skin” was in progress on the floor while dice were rolled on the bed. There was something “shady” about the dice game, for one of the players was always having his dice caught. The musicians were still exhorting to the fifteen or twenty couples that danced. Bedlam reigned. It stopped for a few minutes while one young man hit another for getting fresh with his girl while dancing. The H.D.O. soon ended the fracas.

About two o’clock, a woman from the apartment on the floor below rang the bell and vociferously demanded that this noise stop or that she would call an officer. The hostess laughed in her face and slammed the door. Some tenants are impossible! This was sufficient however, to call the party to a halt. The spirit—or “spirits” had been dying by degrees. Everybody was tired—some had “dates”—others were sleepy— while a few wanted to make a cabaret before “curfew hour.” Mrs. Bailey calmly surveyed a disarranged apartment, and counted her proceeds.

And so the rent party goes on. In fact, it has been going from bad to worse. Harlem copyists of Greenwich Village give them now—for the lark of it. Not always is it a safe and sane affair. Too many evils have crept in, professional gamblers, confidence men, crooks looking for an accomplice for the night, threats of fights with revolvers and razors drawn—any or all of these things may appear in one party. You are seldom certain of your patrons. However, one entrepreneur is always certain of her guests. She invites only members of the Street Cleaning Department and their friends. She extends the invitation Viva Voce from the front window of her apartment. The occupant in the apartment below her once complained to the court of the noise in the course of her parties. The court advised that if the noise were too great she should move. She remained.

At the same time, there may be tragedies. The New York Age carried an editorial sometime ago on a “Rent Party Tragedy.” At this affair one woman killed another woman about a third member of the species. The editorial states in part:

“One of these rent parties a few weeks ago was the scene of a tragic crime in which one jealous woman cut the throat of another, because the two were rivals for the affections of a third woman. The whole situation was on a par with the recent Broadway play, imported from Paris, although the underworld tragedy took place in this locality,—In the mean148time, the combination of bad gin, jealous women, a carving knife, and a rent party is dangerous to the health of all concerned.”

Nowadays, no one knows whether or not one is attending a bonafide rent party. The party today may be fostered by the Tenants Protective Association, or the Imperial Scale of Itinerant Musicians, or the Society for the Relief of Ostracized Bootleggers. Yes, all of these foster parties, though the name is one of fancy. Musicians and Bootleggers have to live as well as the average tenant, and if they can combine their efforts on a business proposition, the status of both may be improved.

It has become in some quarters, a highly commercial affair. With the increased overhead expenses—printing of tickets, hiring the Home Defense Officer, renting chairs, hiring the musicians—one has to make the venture pay.

But the rent parties have not been so frequent of late. Harlem’s new dance halls with their lavish entertainment, double orchestra, and “sixteen hours of continuous dancing,” with easy chairs and refreshments available are ruining the business. They who continue in this venture of pleasure and business are working on a very close margin both socially and economically, when one adds the complexity illustrated by the following incident:

A nine year old boy gazed up from the street to his home on the “top floor, front, East side” of a tenement on West 134th Street about eleven thirty on a Friday night. He waited until the music stopped and cried, “Ma! Ma! I’m sleepy. Can I come in now?” To which a male voice, the owner of which had thrust his head out of the window, replied,—“Your ma says to go to the Midnight Show, and she’ll come after you. Here’s four bits. She says the party’s just got going good.”