American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 36, No. 4 (Jan., 1931), pp. 552-567 PDF

Abstract: Contact between a dominant group and a subordinate group results, through miscegenation, in a third group midway between the two parent-stocks. This third group seeks identification with the dominant group, although the latter may deny such identification. At the same time, because of the characteristics identifying it with the dominant group, it protests against identification with the subordinate group, to which it holds itself superior, and it achieves a status much above that occupied by the subordinate parent-group. This formula of race, which is descriptive of many situations, may be applied with exactitude to two racial islands in America, the Creoles and the Cajuns, both in Alabama. Although quite different in social traits and qualities—in industry, in thrift and cleanliness, in social organization, in intellectual ability, in culture—these two groups are alike in having to occupy distinctive social positions, on the one hand disclaimed by their white parent-groups and on the other hand themselves disclaiming their Negro parents. They equally demonstrate the applicability of the formula of race in America.

552 Recent speculations regarding race have received the benefit of a theoretical structure, or mold, which serves as a highly useful formula in classifying modes of racial contact and in predicting the course of future interracial developments. This formula, the contribution of such sociologists as Park and Reuter, among others, may be simplified as follows: Given a dominant race A, establishing contact with a subordinate race B, there tends to develop through miscegenation an intermediate group C, midway between the two parent-stocks. The new group, C, possessing as it does many of the physical characteristics of the dominant group A, will seek identification with the superior group in its thinking and social intercourse. Although this equality of exchange may be denied the hybrid group by the superior parent-stock, the sense of superiority inherent in the hybrid group because of those characteristics which ally it with group A, as well as a partial recognition of such superiority to the subordinate group B by the superior half of the hybrid’s progenitors, serve as an advantage in propelling the newer group forward to a status far superior to that occupied by the subordinate parent-group. In many instances this marginal situation aids in producing individuals of exceptional ability, even in comparison with types 553 produced by the dominant group, which lacks the peculiar stimulation afforded by the intermediate position of group C.

In the process of miscegenation, of course, the members of the dominant group never anticipate social acceptance while engaged in giving their physical traits to their bastard offspring. That problem, unfortunately, always arises when individuals are found with mixed blood who clamor for social acceptance. The usual result has been that the dominant group, after destroying the purity of both parent-stocks, blandly hoists the bars against these left-handed children in the sacred name of racial purity. The Anglo-Saxon Purity League, and other creations of the “Nordic delusion,” are instances of this untimely attention to the barn door after the horse has fled.

The South Europeans have been more catholic in this respect. The Gaul, or the Spaniard, and the colonist among Latin peoples generally, has in the past found little to choose between his curly-haired son by an aboriginal mother and his other curly-haired son by the wife of his own people. But the Anglo-Saxon tradition is as dominant in this field of racial hybridization as it is in the field of colonial penetration, and for the same reason‚—ts more extensive scope. There are as many obvious instances of the formula and its workings as there are situations involving contact of Europeans with native peoples. Better known than others, perhaps, are the Sino-European of the Pacific Orient, the Hindu half-breeds, dear to fiction and fable, and the hybrid peoples created in this country by contact of whites and American Indians. Who has not heard the musical comedy, or read the short-story, or seen the cinema where there is put forth the sad fate of the beautiful half-breed maiden expiring in devoted agony, after laying down her life to foil the ugly half-breed villain in order that her pure-bred lover and his equally pure-bred white mate might live happily ever after?

Much smoke, some fire; the theme could not be so popular if it had no basis in fact. One has but to turn to the neighboring islands of the Caribbean to find this tragi-comedy of racial hybridization in full swing today. In Haiti there is, and always has been, a clean-cut cleavage between whites, blacks, and mulatto intermediates, with the exception of the period initiated by the massacre of the 554 early French plantation-owners and brought to a conclusion by the intervention of the marines. In Jamaica it exists today, as anyone familiar with the customs of that island or the fulminations of Marcus Garvey can testify. In South Africa one can point to the Reho-bother Bastaards, painstakingly described by Fischer, or to the “colored‚” peoples of the cape as distinctly separated in law and custom from the “natives.”

In our own United States, the land of perfect liberty, where all men are created equal, the situation assuredly gives pause in the application of the formula. There is no ripple of amusement or disbelief from an audience when a speaker who looks like the latest edition of Wendell Phillips‚ “blue-eyed Anglo-Saxon‚” passionately declaims upon‚ “the necessity that all of us black men in America and the world stand together!” For the speaker means a very definite thing, if not exactly what he says, and his audience knows it. Time was when there were blue-vein societies and other organizations of like ilk among Negroes in this country, but they seem largely to have disintegrated, owing to two happy chances of fortune. The first has been that those who were so much like the dominant group as to demand and desire full fellowship to the extent of seclusion from the subordinate group have in great part folded their tents and crept quietly into the ranks of the whites, with no more flurry about it. The other fortunate thing has been the unyielding refusal of the dominant group to accept any of its hybrid progeny, if known as such, no matter how highly infused with the superior strain, into its domestic councils. In this country the public acceptance of the dictum of the sheriff in Show-Boat‚—“One drop of nigger blood makes you a nigger!”—has done countless good for the Negro, as it has served to focus his energies and that of all his potential leaders upon the immediate task of racial survival. There is here no widespread wasting of energies or efforts on the creation and maintenance of an intermediate group.

Yet the formula may aptly be applied to America, land though it be of variation from the expected social norm. If the theoretical implications of the entire situation were not enough to prove it, there are certain points where its full weight may be applied with exactitude. Leaving out of account the instances more highly ex555ploited by the fictioneers and sentimentalists, and even our friends the sociologists, the writer has recently come upon two isolated racial islands which demonstrate as in a microcosm all of the major problems of race in the country at large.

Baldwin County, Alabama, is the seat of the first of these racial islands. The county itself presents one of the most remarkable hodgepodges conceivable even in the America in which we live. There is a large Greek colony, communistic in structure, located at Loxley. There are French, Polish, Italian, Scandinavian, German, Bohemian, and Croatian colonies. Besides these foreign-language groups, there are two religious colonies in a settlement of Quakers near Fairhope and another of Amish Mennonites, a sect of the Hooker Mennonites. The ever present Negro is here as tenant, small-farm-owner, and laborer in the numerous turpentine and naval-store plants in the woodlands and swamps.

At Fairhope is the well-known Single Tax Colony, made prosperous by intelligence as well as by a fortunate rise in real-estate values facilitated by the development of the Gulf Coast region and the recent construction of the Cochrane Bridge across Mobile Bay. Also located in this little town which resembles Indiana more than Alabama is the Organic School, where the devoted disciples of Marietta Johnson pursue the ideal of a “free‚” school with a zeal found only in idealists wedded to a novel idea.

To reach the home of the peculiar racial group in question, one leaves the Old Spanish Trail at the eastern head of the Cochrane Bridge, and drives south through Fairhope along Mobile Bay. Ten or fifteen miles beyond is the pleasant little village of Magnolia Springs, and one is in the sandy Gulf Coast soil where these people have their farms and community life. They call themselves “Creoles‚” and their white neighbors qualify the term by calling them “Nigger Creoles.” The question of Negro blood has long been a sensitive spot with the Creole population of Louisiana and other southern states, but in Baldwin County it means only one thing to the dominant white class: some degree of Negro extraction.

The very houses announce a different community. They are 556 small and weather-beaten, but with none of the ugly rawness characteristic of the newer cottages of white farm-owners, or the destitution usually noticeable in the Negro plantation cabins. Picket fences, whitewashed and prim, surround the yards, which are neat and orderly. The farm land around shows evidence of careful tillage.

Our first stop was to inquire at a farmhouse as to the road to take to reach the nearest Creole school. Directions were crisp and exact. The women who directed us, an elderly woman and a girl, were typical of all the women we saw in this community, with brown skins, black hair, and pleasant features. They spoke with the dialect of the southern white lowlander, and with the same inflection and intonation.

A stop at a little crossroads store where the young Creole clerk volunteered more information led us still farther into the intricacies of life among the Magnolia Springs Creoles. The clerk was a small man whose complexion had a hint of reddish brown, and he was one of the few men in the community who bore a French family name. He claimed to be the great-grandson of an officer in Napoleon’s Grande Armée. He had come to the Baldwin County community from across the bay. He gave as his reason the decay of the Creole community in Mobile County, and stated that this disintegration was almost complete.

I was able to visit this other Creole community in Mobile County, a community located on Mon Louis Island some fifteen miles south of Mobile. There the decomposition of the system was very evident, noticeable in an increasing number of intermarriages with those who claimed no other race than Negro, and by the acceptance of teachers known to be Negroes if they were sufficiently light in complexion to “pass” for Creoles, and if they were good Catholics. The Baldwin County Creoles, we were told, would never accept a Negro teacher, Catholic or not. One innocent young man had been sent to the Creole community as a teacher some years in the past, only to be forced to leave precipitously soon after his appearance at the schoolhouse. For all this, it is a fact that forty or fifty years ago the Creoles of Baldwin County had Negro teachers and made no objection. Apparently this indicates that the struggle for sur557vival has grown more acute, and outside pressure has forced them to a greater group consciousness as a survival measure.

The first Creole school was an ordinary building located near a small Catholic chapel. The teacher was a young white man who looked at me speculatively as we approached. As we were inspecting the Negro schools of the county, and the county superintendent had listed the Creole schools among this number, the white member of our party suggested that I should stay at this school while he went on to the next one to administer the tests we were using as a means of discovering pupil achievement. The teacher was clearly at a loss. At first hand he was unable to determine with which group I was to be classified, and he was at some pains not to insult me if I were a Creole. Finally, he came bluntly to the point.

“What do you call yourself?”

In some surprise I hastened to give what I thought was the obvious answer: “Why, I’m a Negro.”

The need for hedging was gone. “Well, I’ll tell you; of course I’m not prejudiced, but if some of these Creoles heard that a nigger was up here giving tests to their children, I don’t know what would happen.”

There is, perhaps, little need to add that it was decided that the white member of the party should administer tests at both schools.

The children proved to be remarkably alert. They scored above the standards expected even of white children of their age and classification, on the basis of nation-wide standards. These standards are based on the performance of children representative of urban as well as of rural systems, and rural children generally may be expected to score below these standards. The contrast in their work was all the more striking because of long months spent in handling classrooms of plantation Negro children, whose preparation for the type of response called for by the tests is especially poor.

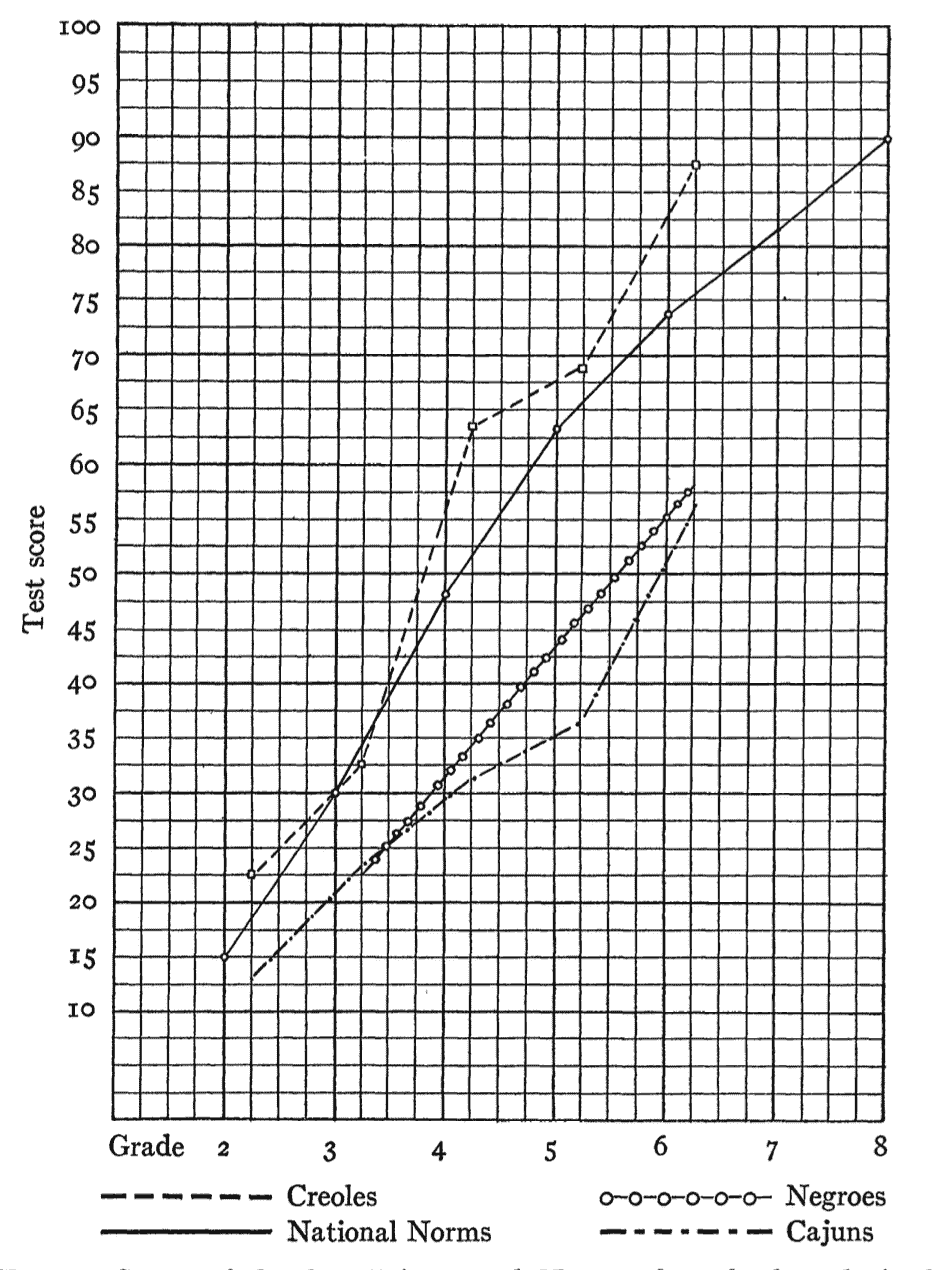

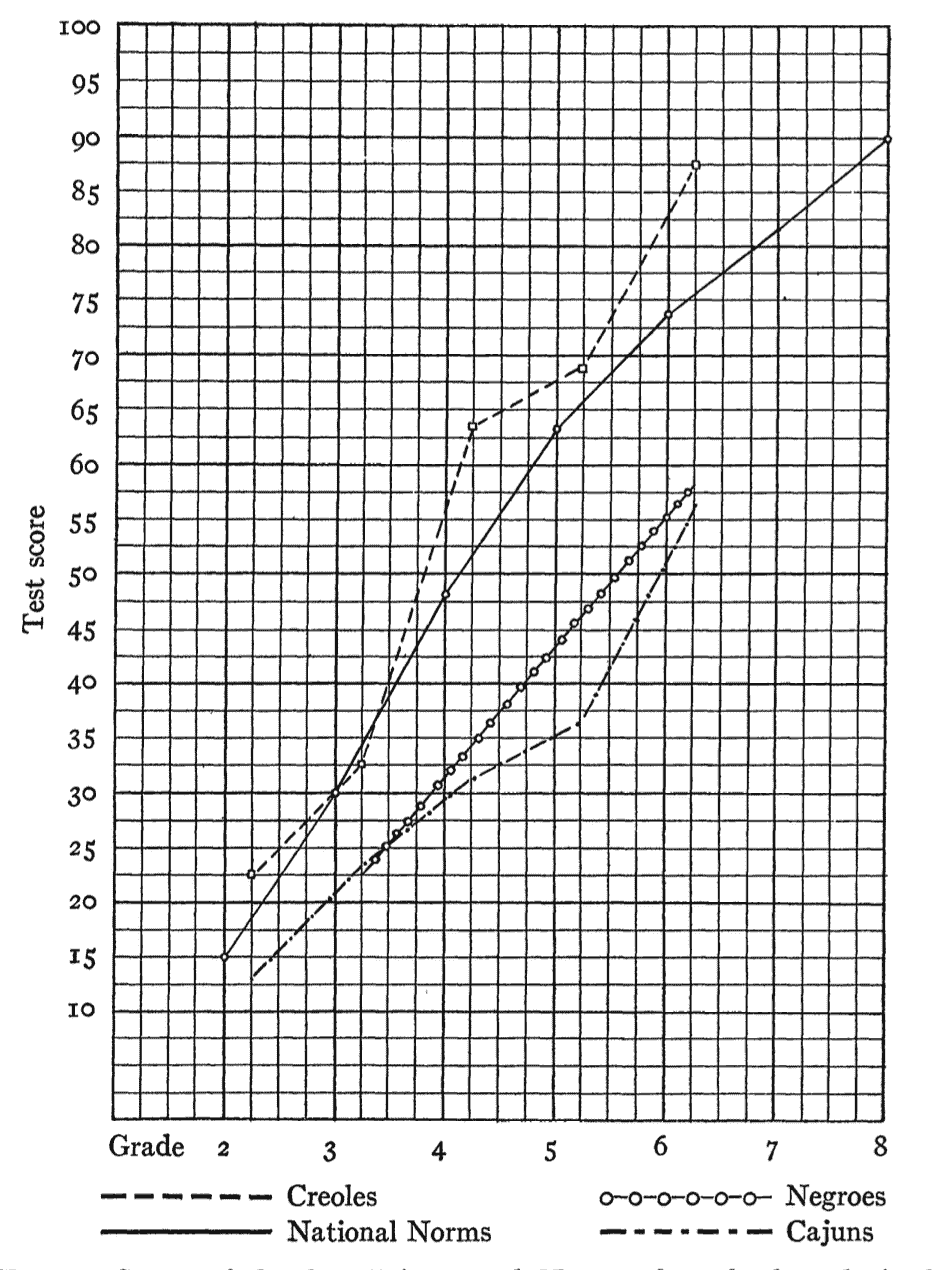

In the accompanying figure the results of tests given to Creoles, Negroes, and Cajuns is graphically displayed, in comparison with the national standards based on pupil performance. With the exception of the third grade, where the difference was but slight, the Creole children exceeded the national standards for each grade. 558 for the seventh and eighth grades were unobtainable because the Creole schools did not have these grades.

Why are these children superior? They have excellent teachers, but these can hardly be judged to be better than those in the large white consolidated schools in the county. The fact that both schools are small should, with the fact that the clientele is altogether rural, militate against superior performance. The significant fact is that with all of these negative conditions which ordinarily would be ex559pected to result in a low score for the children they make an exceptional score.

In color, the children ranged from shades of brown to white. The darkest of the children could have found entrée into more cosmopolitan circles where the presence of dark South Europeans is usual. Children may be observed attending white schools in Mobile, just across the bay, who are every whit as dark in complexion, and whose hair is as curly as is typical of the Creole children. There was a startling similarity in their physiognomies, regardless of the wide variations in color.

From the first school we went on to the next and last Creole school. Another white teacher, the wife of the man who presided over the other school, welcomed us into her neat room, looking for all the world like a little Hoosier schoolhouse set down in southern Alabama. From the statements of our guides, as well as the opinions of the male teacher, we had expected to find a group much different from the first group, for the second school was reputed to be the more aristocratic of the two. There prevailed even in this little community of some two hundred families a cleavage along lines of color, and while the presence of darker children, we had been told, was tolerated, it was pre-eminently a school for the Creole elite, where distinction was based on lightness of complexion. To the eye of the uninitiated, no such cleavage was evident. The same blue eyes, brown skins, flaxen hair, curly hair, and all other combinations seen at the first school were present here. The distinction is one made largely by the heads of the families which control the two schools. It would be very easy for these people to have a well-equipped central school to take the place of the two temporary structures now used. Two things prevent. In the first place, they are afraid to consolidate the schools and accept state aid because this might place them under the control of the county superintendent even more definitely than they now are, and that functionary could then assign Negro teachers to their school. In the second place, the lighter Creoles of the second school’s trustee board will not agree to send their children to the other school where the members of two or three darker families are represented on the trustee board.

560 This situation results in some interesting developments. Children living within a stone’s throw of the first school drive five miles past it to attend the other school. Often, we are told, a family in which a light complexion predominates will bring into the world a child darker than its parents or the other children in the family. The child so unfortunate occupies a different position in the household. One father had a son much darker than himself. When he left the Creole community he passed his son off as his chauffeur, and so rose superior to the barriers of race in his own case.

The children in the second school were as able as in the first. Again one must credit the efficiency of a good teacher. There are those, of course, who would prefer to explain the superiority of these Creole children on the basis of their white blood. But they are superior to white children, and the situation existing with regard to the ability of children in the other racial island visited does not sustain this impression.

All of these Creoles are Catholics, and staunch believers. They feel themselves immeasurably superior to the “turpentine niggers‚” around them, and so they are in many ways. They are not allowed to enter the white schools, and so their education is confined to the sixth grade of the local schools. They could send their children to the Negro high school for Baldwin County, located only twenty miles away at Daphne; but no Creole would lower himself by allowing his child to go to school with “niggers.” As a result, they are completely cut off from outside association, and their persistence for some time to come seems to be guaranteed by their inability, on the one hand, to enter into another world, and their refusal, on the other, to assimilate with the Negro group.

At community dances and social affairs white men are welcomed readily, and the results for continued miscegenation are obvious. In the disintegrating Mobile County community the decay had reached the point where the young men were breaking away, leaving behind only women, children, and the elderly folk of the tribe. There were in the latter community several notorious cases of concubinage, cases of which existed but were not so openly arrived at in the Baldwin County Creole community.

These “Creoles‚” are in many ways an amusing people, when one 561 considers the intertribal prejudices and ideas of race that bind them. Yet the humor with which they may be viewed is more pathetic than ludicrous, for any observer interested in a well-knit rural community can appreciate the struggle they have made and are making for status. The level of their social and economic life is on a higher plane than that of the tenant and laboring Negroes of this rural countryside. If the Creoles allowed the bars they have put up to be relaxed even temporarily the unique life of the community would be gone forever. Now they are Creoles, with pride, and the heartening sense of being a people with a tradition and a past. If they weaken they will be only Negroes, and perhaps the community will be flooded by the ignorant folk around them. There can be no doubt that there is a strain of Negro blood in the community, however, although it is increasingly attenuated, owing to their positive refusal of association with Negroes and their partial acquiescence in miscegenation, so long as it is conducted with whites.

There is a legend in the countryside that the community goes back in its history to the days when the Spanish Main harbored numerous pirates and freebooters in the little inlets along the Gulf Coast. A portion of these Carib marauders, so the legend goes, maintained a rendezvous on the eastern shore of Mobile Bay, where these people now live. There is a little bay that bears the name of one of the largest families in the community, and that name belonged to a distinguished member of the piratical elect of the days of Jean Lafitte and his predecessors. To this little Eden, so the story goes, the robbers of the sea brought their spoils for division. Naturally, a considerable portion of these rewards of piracy were in the nature of feminine consignments. Their women were of all races: Negroes, Spanish, French, and English. The hybridization begun in this way has produced the people here described.

But for all this storied past, there is nothing romantic in the attitude of the white people who are their neighbors. They look upon the Creoles as a vile people who have violated, however unconsciously, the dogma of race purity; and so they are despised and rejected of all good Baldwin countians. Their future is uncertain. Perhaps they will disappear in the course of a few years, like the Mobile County communities whose decay the young Creole lament562ed. When it crumbles, some members of it will leave the country to be swallowed up in the whites, and the remainder will submerge themselves in the toiling Negroes who are all around. Until that time comes, however, this little spot will continue to be a place where the workings of a tri-racial system may yet be observed. Until the present it has been neglected by both the probing hands of the sociologist and the sentimental fabrications of the short-story agonizers. As they exist today, unmistakably hybrid though they be, they are yet a peculiarly superior people.

Across the swamps of the Tensas and Alabama rivers, now bridged by the ten-mile causeway of the Cochrane Bridge, is the city of Mobile. Thirty miles north of this old center of early French and Spanish explorers are several detached and isolated communities of another hybrid people who call themselves Cajuns. Those in Mobile County are probably migrants from the main body of this people, which numbers several thousand in Alabama alone. There are many others in the counties which lie immediately to the north—Clark and Washington. In the latter two counties their numbers are considerable enough to constitute a difficult problem, necessitating the maintenance of a tri-racial system of schools which is productive of every kind of administrative tangle for harassed school officials. Whether the Cajuns of Alabama bear kinship to those of Mississippi and Louisiana is a matter of question. The word itself is a corruption of “Acadian‚” or “Arcadian” and their derivation is claimed by the historians of Louisiana to be from those French-Canadians dispossessed by the British in the eighteenth century and immortalized by Longfellow. Not a single person could be found in the Mobile County community, however, who knew of this origin, or claimed it. They admit readily the racial heritage from the Indian, but deny as strongly as the Creoles of Baldwin County the presence of any “Negro taint.” A singular thing is that not a single family as represented in the Mobile County community bears a name indicating Latin derivation. Family names are all good old Scotch-Irish-English patronymics; a school roll showed such family names as Smith, Terry, Jones, and Carter.

563 Aside from their common status as intermediary racial groups, there is little between the Creoles mid Cajuns to indicate any relationship. The Cajuns are almost universally Baptists or Methodists, although, as a matter of fact, they are by no means enthusiastic devotees of these sects.

Indeed, it is difficult to find anything about which the Cajuns grow enthusiastic. The churches are maintained only as missions, and by outside mission boards. There is certainly no riper field in America for missionary endeavor. The neat houses and lots characteristic of the Creole community in Baldwin County are replaced in the Cajun community by wretched cabins, giving an impression of squalor more depressing than can be seen in any Negro cabin in that part of the county. On every tiny veranda women sit in idleness while untidy, half-clad children play in the sunlight. The women are rouged vividly, regardless of age, and the artificial color of their faces contrasts oddly with the general neglect attending their costumes and the background furnished by the wild and tangled countryside around.

We entered a school which, we were told by a bedizened old woman who sat calmly smoking a pipe on the veranda of a nearby cabin, was also the local Methodist church. With the exception of Rosenwald-built schools, Negro schoolhouses in Alabama are generally decrepit, but in cases which occur frequently the school is taught in a church which is always a substantially sealed building. The Cajun church-schoolhouse, however, was a sad affair. The ceiling was furnished by the shingled roof, and it was in such disrepair that numerous little “tents of blue” appeared through the cracks where shingles had been. The single weather-beaten walls were streaked with large cracks, and the rough board floors showed gaping holes that called for some little care in walking around the room. In such a building as this ventilation would never be a problem for the teacher, if fresh air was the only thing needed. A little heater stood in one comer, but its utility in even moderately cold weather was doubtful. The condition of the building was significant because in the South the church is usually a reflection of the level of community enterprise in rural areas. Many Negro schoolhouses are in a condition as poor as this Cajun school, but one will rarely if 564 ever find in the entire countryside so ramshackle a structure used by Negroes as a church.

The children were unkempt and remarkably rude. Where the Creoles of Baldwin County had used the dialect of the better-class whites, these Cajun children used a lingo which had none of the subtle, softened graces of elision characteristic of the Negro field hand, but with all of the nasalities of “poor white trash.” Their stupidity was a little shocking, even to one accustomed to backward children. We have noted how they compared with the Negro children and the Creoles, by grades. When it is remembered further that the Cajun children averaged a year over-age even when compared with the Negro school children, who were far above normal age levels for their respective grades, their poor showing becomes more evident.

During a lull in the inspection one of the larger boys—a frecklefaced, red-haired youngster who looked akin to the tribe of Huck Finn—was asked, “What do you people call yourself?”

“We’se Cajuns, we is. We’se Injuns an’ white folks, all mixed up. We ain’t never had no nigger blood in us.”

“Yes, but why do you call yourself by that name? Where does ‘Cajun’ come from, and what does it mean?”

“We’uns don’t know.” But he did know that he had no “nigger” blood in him, although a little girl sat in the next seat whose crimped hair was never inherited from the noble Red Man.

In addition to the size and condition of rural churches, an unfailing index to the status of a rural community may be found in the graveyards. The burial plot attached to this church was unfenced, and the only signs to show the resting places of the Cajuns’ dear departed consisted of little mounds, with here and there a broken pitcher or half-filled medicine bottle, the label long since worn off by the elements. There was not a single gravestone or board in the plot. Even the pieces of broken china, ever present in the typical Negro burial ground as mementos of the last struggle for life and the faithful care of the weeping relicts, were indeed fragmentary here. The thicket in which the plot was located did serve some utilitarian purpose, however, for in the absence of conveniences the 565 children had open and shameless recourse to the privacy the graves of their ancestors afforded.

In complexion the children ran all shades on the scale from brown to white, as in the case of the Creole children. However, there was no homogeneity of feature such as that which seemed to brand the members of the little Creole community as akin, regardless of a difference in complexion. There were some small children who might have been taken from the backs of Indian squaws on the plains, but the general impression was one of a bewildering variety of all sorts of racial admixture, with Negroid features accompanying blue eyes and flaxen hair, ranging to classic features framed by a mop of unruly hair shading a dark skin.

Inquiry revealed the fact that but few of the Cajuns own their land. They live in the barren hill country where eight dollars an acre is a high price for land which has been cut over for timber and will grow sparse upland cotton and enough sweet potatoes to keep a family alive for a year.

Like the Creoles of Baldwin County, they are barred from all social intercourse with the whites, and refuse to ally themselves with the Negroes. In the case of the Cajuns, however, this works entirely to their disadvantage, for while the Negroes hate the Creoles for their superior attitude, they merely despise the Cajuns. They feel that they are far above these hill people, for even the poorest Negro tenant has a share in a strong community life, goes to church regularly, and takes some pride in his personal appearance and that of his children. The most poverty-stricken of these Negro tenants in the surrounding countryside will refer with a delicious sense of superiority and scorn to “them dirty Cajuns;” and the Creoles, when asked if they were a kindred people to their fellow-hybrids of Mobile County, were quick to deny the slander.

The Cajuns will not now accept Negro teachers, although in times past they made no bones over accepting women who were of light complexion. Their schools, however, are listed officially with the Negro schools. The surrounding whites object to white women going into their community to teach, the objection, as one native informed me, being due to the fact that there had occurred several 566 cases where these white teachers had married Cajuns, thus violating the code of racial purity.

As the backwoods fastnesses of the Cajuns are gradually penetrated from year to year by good roads and other agencies of extra-world contacts, their group is undergoing a rapid process of decay, as with the Creoles of Mobile County who are now almost a thing of the past. In these Cajun communities where the families are brought in open contact with the white world the demoralization seems to be even more thorough. The Creoles simply disappear, while echoes of the Cajuns linger on in tales of licentious conduct, concubinage with both white and black men, and altogether a lingering survival of the disorganization now patent in the community, but even more raw and unpleasant when exposed to the probing of forces from two sides.

After the Creole and Cajun communities it is something of a relief to find one’s self back in Mobile, in a world where a bi-racial situation is provocative of enough perplexities for the ordinary man. In this safe haven of comparative security, where I know every Negro as a potential friend and every white man, if not as a potential enemy, at least as a person of whose gestures I must take wary cognizance, it is instructive to reflect that thirty miles from this city, in opposite directions, are to be found two little racial islands that mirror the larger whole in many ways, yet with a concentrated complexity difficult to imagine aside from reality. Here in this little thirty-mile circle are two hybrid groups, one firm, industrious, thrifty, clean, and intelligent, bound together with the strong discipline of Mother Church, yet shot through with distinctions as vital to them as those which separate me from other men in this city. The other hybrid group is almost completely disorganized, its people thriftless, untidy in person and in their homes, unintelligent, without benefit of clergy except for a feeble mission effort for which they have no enthusiasm and from which they gain little in the way of either religious consolation or social unity.

How can we explain the riddle? Manifestly the tonic qualities of the white blood, so boasted in the past as an explanation of progress, has no right to be claimed as the basic factor here. It is absurd 567 to say that the Baldwin County Creoles are superior because they have so much white blood, for the Cajuns are as much favored or handicapped by this precious elixir as the former people. At any rate, these islands show that the formula of race may be demonstrated even in the present in this country. The difference between these two groups in social progress may be due to their religion, and its venerable tradition, or lack of it. It may be due to a strong sense of group solidarity fostered by this religious bond, lacking in one group as it clearly is. Whatever the explanation, certainly one needs some other explanation than that of hereditary racial superiority or inferiority to account for the vast social distance that separates these two racial islands.