The Southern Workman, vol LI, no. 2, Feb. 1922, pp. 64–72.

64 The thought realm in which the two million Negro women in the United States, gainfully employed, live and work, vibrates with pathos and humor, determination and true heroism, belief and expectation that with the coming years, they too, as a group, with training and larger opportunities, will come into their own as real women.

The three types of occupations in which the majority of these women are engaged are (1) domestic and personal service, (2) agriculture, (3) manufacturing and mechanical industries.

To-day they are found in domestic service, nearly a million strong, with all their shortcomings—their lack of training in efficiency, in cleanliness of person, in honesty and truthfulness, and with all of the shortcomings of ordinary domestic service; namely, basement living quarters, poor working conditions, too long hours, no Sundays off, no standards of efficiency, and the servant “brand.” In spite of migration during the World War they are found on the farms, with all of the inconveniences and health hazards of Southern plantation life, in larger numbers than in domestic service. Before the World War there were over 67,000 of them in the unskilled processes of the manufacturing and mechanical industries and 3000 in the semi-skilled processes. These numbers were greatly increased during the war. In 152 plants visited in 1918-19, by Department of Labor representatives, more than 20,000 were found employed.

During the past twelve months some decided changes affecting Negro women have taken place in domestic and personal service. For instance, in Detroit, Michigan, to-day, from eighty to ninety per cent of the calls for domestic workers are for white girls. The average wage in that city for general houseworkers is from $ 8 to $12 a week as against $15 to $20 a year ago. Women working by the day receive from $.40 to $.50 an hour as against $.60 to $.70 one year ago. The calls for office, elevator, and stock girls are no longer for Negro girls.

In Washington, D. C., with the fixing of the minimum wage in the hotels, restaurants, etc., at $16.50 for a forty-eight-hour week, and the increasing number of available white women, Negro women were to a very large extent displaced. Wages for 65 domestic service for the rank and file have fallen in the past twelve months from $10 a week without any laundry work to $7 and $8 with laundry work. In the parlance of the women, “general housework” now means “cook, wash, and ine (iron).” The numbers driven into domestic work are very large. At one employment agency in this city there are often as many as 200 Negro women a day applying for work. A large majority of them are untrained, inefficient, and poorly equipped with the one thing needful—a good reference.

Only two of the Washington laundries are to-day paying the minimum wage. The average wage in the other laundries is $9 per week, and a few workers get as little as $6. Ninety per cent of these laundry workers are Negro women. As soon as some of the laundries began to fear that they would be forced to pay the minimum wage they began to ask the employment bureaus about the possibility of obtaining white girls. Now that they are not paying the minimum wage they are perfectly satisfied with Negro women. A few of these have been in the laundries from fourteen to thirty-eight years, working through from the flat-work department until they are now “finishing” shirt-bosoms—which one who understands must term really artistic work. In Los Angeles, California, Negro women cooks get from 66 $60 to $100 per month, chambermaids from $40 to $75, nurses from $50 to $75, mothers’ helpers from $20 to $40. Day workers receive from $.45 to $.50 an hour. These women are, however, through the unions, excluded from even the laundries.

Some very evident changes have come about in personal and domestic service during the past twelve months, and yet there is much the same restlessness and change from one employer to another; much the same wear and tear on households and housewives; many of the same old customs and conventions. The bond between mistress and maid in many cases is not sufficiently strong for the mistress to learn her maid’s surname or her address. Neither seems personally interested in the other and often neither knows, even when they separate, just what the other has been thinking. When one deeply interested in the whole problem analyzes the conditions and sympathizes with mistress and maid sufficiently to get the whole truth, she must conclude that in too many cases the feeling of each borders on real dislike for the other. Neither has for the other that priceless possession—confidence.

Recently a gentleman applied to an employment agency for a maid or, more correctly speaking, a general houseworker. Upon being asked how many there were in his family, he said, in a somewhat hesitating manner, “Just two in the family, except two boys who don’t amount to much—one is six years old and the other is eight.’’ No idea of taking advantage of anyone entered his mind, for his were the thoughts of a man! but the women domestics who heard him at once came to the conclusion that he was trying to “slip something over.” On the other hand, a lady advertised for a maid and fifteen came at different times during the day to see her. She engaged every one of them to begin work the next morning and not one of them “showed up.” When maids wish a holiday or Sunday off, death in their families, falls by which they are seriously injured, automobile accidents, faked special-delivery letters (especially when they live with the employer’s family) annual meetings of lodges in distant cities, and all sorts of other make-believe excuses are given. The night they are paid off they often arrange everything for breakfast, saying they will be back in the morning, but they never return. Often, on the other hand, when a maid applies for a place, if she is not suitable, she is told by the lady of the house that her former maid has just come back.

Letters, cards, telephone calls, the people themselves, bespeak the pathos, the restlessness, the ignorance, the inefficiency, the absolute need of the standardization of domestic 67 service as an occupation or industry, and also the absolute need of domestic-training schools in connection with public employment agencies.

A woman owning over a thousand acres of land in the Black Belt of Alabama wrote me, saying:

Farm conditions are as bad as we have ever seen them. The cotton crop is very poor. Women can pick on an average of from 85 to 110 pounds of cotton per day, for which they get 40 cents a hundred. The peanut farms also furnish some work for women at the rate of 50 cents a day. They pull up the peanut bushes and let them dry. The bushes are then taken to a steam peanut picker which picks off the peanuts; these are then sacked and sent to the factory.

Down here women do almost any kind of work on the farm from handling a two-horse plow, and hoeing and pulling fodder, to cleaning new ground. Women in domestic service here get from $7 to $8 per month.

Allowing much for migration and giving due credit to the General Education Board, the Slater and Rosenwald Funds, the Jeanes supervisors, and the farm-demonstration agents, who are doing a great work in rural districts of the South, there are many thousand Negro women on the farms to-day eking out such a bare existence as is described in the above letter. They are out early in the morning afoot and on horseback going to near-by fields and, in many instances, on wagons going to fields four and five miles distant. If the fields are near by, they hurry home in the heat of the broiling sun to cook their families’ 68 dinners, often over a blazing fire on the hearth, and after dinner they return to the fields in what seems to city people sweltering heat. They tarry late in the fields because, as they say, they can work better “in the cool of the evenin’.”

In many sections almost the only recreational or social contacts enjoyed by such women come through the monthly church meeting, the occasional burial of a friend, or the annual trip to town at cotton-seed time. Better prepared ministers, more missionary school-teachers and welfare workers, and many district nurses would make the life of the average agricultural woman worker more endurable.

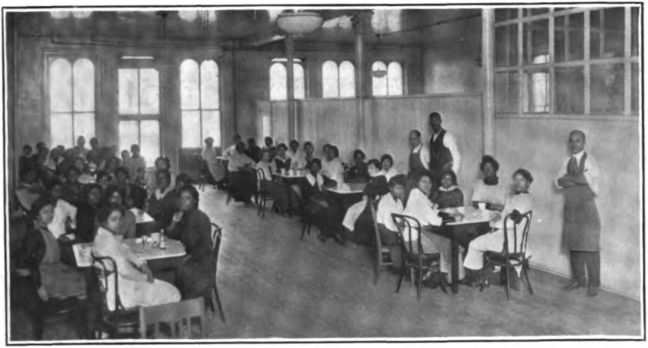

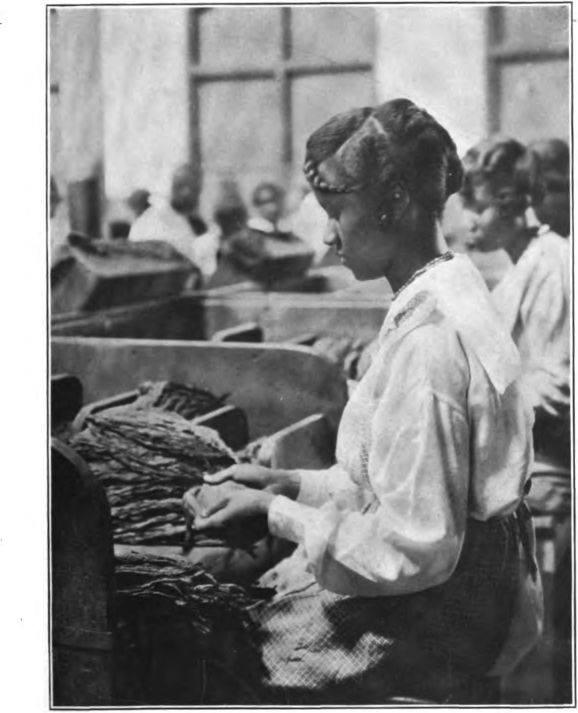

Many well-informed persons are apt to think that there were no Negro women in manufacturing or mechanical industries until the World War. On the contrary there were and are still some thousands of Negro women in the cigar and tobacco factories of the country. They are poorly paid, of course, their wages ranging from $6 to $10 for a sixty-hour week. The work is dirty, and most of the factories are poorly ventilated, being without an air shaft for the expulsion of the dust; the result is that the tobacco fumes and dust almost suffocate new workers. Then, the work being more or less seasonal, women are sometimes out of employment for weeks at a time. In most tobacco factories the only seats for the women are boxes or stools without backs; and in a few factories women stemming 69 tobacco sit flat on the floor, humming a tune while they work. Even fairly respectable lunch rooms and decent toilet facilities are lacking.

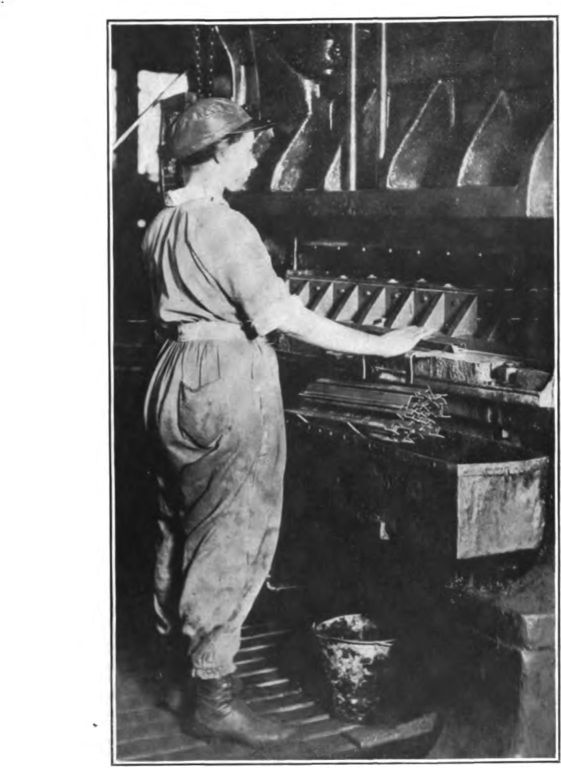

Before the World War unskilled Negro women workers in small numbers were in the clothing, food, and metal industries. They were to be found especially in slaughtering and meatpacking houses, crab and peanut factories, and iron, steel and automobile industries. They were also working in furniture and shoe factories, printing and publishing establishments, and in cotton and silk mills. There were semi-skilled workers in electrical-supply, paper-box, and rubber factories, and in the textile industries. Finally there were a few skilled tailoresses, tinsmiths, coppersmiths, and upholsterers. The story of their entrance into industry in large numbers during the World War is too familiar to warrant repetition here. The 70 part they played in winning the war will probably not be told for many years to come.

Just before the beginning of the unemployment crisis the Women’s Bureau of the Department of Labor made a survey of Negro women employed in 150 plants in 17 localities of 9 States. In those plants, covering food, furniture, glass, leather, metal, and paper products, tobacco, and textiles, there were 11,812 Negro women employed. Some of these were even making and decorating lamp-shades; some were making cores in foundries; and others were competing successfully (according to their employers) with girls of many years’ experience in the textile industries. Still others were serving as stenographers, typists, etc., in two large mail-order houses in the Middle West.

The questions in the minds of us all are these: How many of these industries still employ Negro women in appreciable number in the skilled and unskilled processes? Are there many Negro women in other industries? And how will Negro women bread-winners, unused to domestic service, weather the storm of the unemployment depression? Information to date from industrial plants in the East, West, North, and South indicates that a large number of Negro women have lost their places within the last twelve months. One large garment factory in the Middle West, one of the first to take on Negro women and 71 one that seemed proud of its experiment, says now, “We have discontinued the use of Negro women.” A Southern mill that used some Negro women before the war says, “We use Negro women only occasionally now for odd jobs.”

In spite of such reports, at least some Negro women are still employed in factories. For instance, the Virginia and Maryland crab factories employ 5000 to 8000 of these women. Some of them, now forty or fifty years of age, have been in the same factory since they were twelve years old. Crabs are brought in barrels placed in large, iron, crate-like kettles, which are set down into steam for the purpose of cooking the crabs. A newer method is to use cars with seven barrels of 72 crabs to a car. The cars are run on tracks into a steam chest which cooks the crabs in a few minutes. When they are cold each woman receives a certain number of shovelfuls at a long wooden table, or, in a more up-to-date factory, at a better arranged table for two workers. The woman sits on a box, or a “backless” stool, strikes a crab one blow with the handle of a small knife with curved blade, taking off a part of the shell, and, often without even looking at the crab, cuts out what is called “the dead man” and then the white meat, which falls into a pan, and the dark meat, which falls into another. The work is done so rapidly that women pick from forty to seventy-five pounds a day, thus earning $3 or more a day. The crab factories are built over the water, many of them having cement floors. A woman who has worked in such a factory for many years, upon being asked about the healthfulness of such an arrangement, said, “Yes, ma’am, the floors gen’ally fills you full o’ rheumatism. Some mo’nin’s I kin hardly git out o’bed, I’se so stiff and painful.” In spite of the lack of any arrangement that might be called sanitary, except in a very few factories, one never saw a happier group of workers anywhere than the Negro women in the crab factories.

Women who have never worked out and whose husbands have lost their jobs after ten or twenty years’ service on the railroads or in other places, and others who have worked out but have not been inside of an employment agency for twenty-five or more years, are now trying, through such agencies or through friends, to find a day’s work—cleaning or washing or sewing; hair-dressing or manicuring; acting as agents for selling goods; assisting undertakers; or doing anything else whereby they can earn a living. Struggling against lack of training and against inefficiency, restricted in opportunities to get and hold jobs, more than two million Negro women and girls are to-day laboring in domestic service, in agriculture, and in manufacturing pursuits with the hope of an economic independence that will some day enable them to take their places in the ranks with other working women.